“The other benefit is that the five PTEs are very focused on pursuing their own local agendas - why wouldn’t they be? So there is a tension between what Liverpool, Manchester, Sheffield, Leeds and Newcastle want.

“The other benefit is that the five PTEs are very focused on pursuing their own local agendas - why wouldn’t they be? So there is a tension between what Liverpool, Manchester, Sheffield, Leeds and Newcastle want.

“In future, under Rail North, all the 29 transport authorities in the North will come together and be forced to speak with one voice. That is one reason why Rail North has been so successful in influencing the ITT for Northern, because they have lobbied government coherently as one group.

“Until Rail North there was no coherent view across the region. Now the northern transport authorities have to get in a dark room and work out how to function together, making compromises. To central government it means the North presents a much more joined-up view, which has to be a good thing.”

Hynes does not think that will necessarily result in an easier or less bureaucratic ride for him. But he does see it leading to more money in the rail pot.

“Politicians like spending money on things they control. When Rail North has focus on both franchises, I think it will want to spend more money on them.

“For example, Greater Manchester has been spending its trans-port money on building a fantastic tram network. So it has not been spending loads of money working with us on improving rail services and stations in Greater Manchester. As a result, station quality is pretty basic. West Yorkshire doesn’t have a tram, so it has spent a lot of money with us, upgrading the local network. And it shows.”

David Brown does not see Transport for London as the role model for devolved transport authorities.

“I spent time understanding what Transport Scotland has done with letting out franchising. It has a lot of local transport authorities across Scotland, so is probably more akin to what Rail North is trying to achieve, rather than TfL. Because we cover a very big geography, at the moment we are just looking at rail franchising.”

So what’s in it for his employer, Merseytravel, which releases Brown for up to two days a week? The Merseyrail franchise represents around 5% of the total northern rail network, and is not part of Rail North’s two-franchise remit.

“We have a clear long-term strategy for rail on Merseyside, with a long time left on our current concession. We have interesting investment coming in new rolling stock, station improvement plans and extensions to the system. So a lot of the experience we have here is feeding into Rail North. On our local city lines, we are looking to get a similar quality to what we already receive from Merseyrail. At the moment Northern is not as good, not as frequent, and the customer service is not as good. For us, we are hoping to get a raised standard.

“We spent a lot of time making the wider economic case for the replacement of Pacers. All customers said to us that we needed more trains and better trains. Our train stock was old and decrepit. That became a mantra for us, focused on Pacers. A lot of those trains are full. But there is actually no financial case within the railway for replacing the Pacers with anything - they are so cheap.

“The case had to be made in a wider way. It was about the wider economic benefit, and that is where - as a bigger Rail North - we could more effectively influence MPs and the Department. And it worked. The result is the tender specification including a minimum of 120 new vehicles. We are very clear about that being a minimum. And we are very clear that these are new-build - we do not want refurbished Vivarail Tube trains. I have seen quotes from the DfT, also saying that “new” really does mean new, not second-hand from anywhere else.

“And they have to be diesel-powered. The growth potential in the North requires that, because the electrification programme is not going to deliver here. Electrification of TransPennine has been moved back, so there will be no cascade of suitable trains. We cannot wait for that to happen.”

Brown was speaking in the aftermath of a remarkable weekend for the transport system on Merseyside. One million people had attended a celebration to mark 175 years of the shipping line Cunard. Although the waterfront event happened over three days, most visitors were concentrated in a two-hour period on a Bank Holiday Monday.

It was one of the largest spectator events ever held in a single location in the UK. The Olympics were bigger, but spread over a fortnight and at multiple sites. The visiting Tour de France was bigger, but with audiences spread across Yorkshire.

“It’s a good example of where local devolution can help with major events,” explains Brown. “Because we have a concession, a financial arrangement with Merseyrail as operator, it has enabled us to put in all the capacity available, all in six-car formations instead of the normal three.

“We can manage stations, close stations, put in the resources to get a proportion of those one million visitors away from here by train very quickly. That would be much harder elsewhere. We have that flexibility. It has worked better than ever before, but it still required Northern to get a special derogation from central government to move vehicles and so on.

“Liverpool City Council wants to do big events like this. One of the reasons they can do that here is a really good local rail system. We’ve put a lot of effort into customer service. People have moved away from the Cunard event by train with smiles on their faces, and they’ve paid a fare. That’s the ideal railway, isn’t it?”

“Rail North can understand the local economics better,” agrees Hynes. “We are encouraging Government to see rail spending as an investment, rather than as a cost. The Department has a business case to expand rail in the South because it is commercially viable. Up North it doesn’t - every time you expand the rail service, it costs you more money. So a cash-strapped central Government is never going to be particularly keen to drive growth, rather than merely accommodate it.

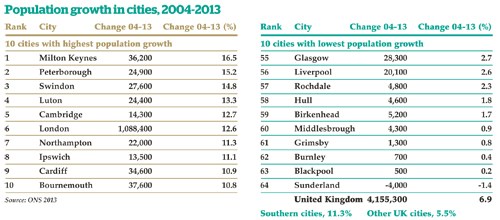

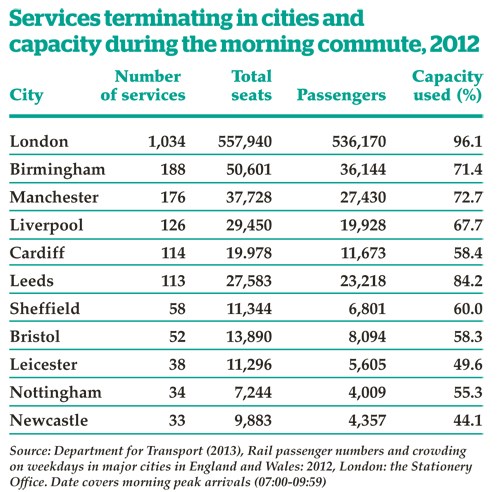

“The Northern cities take a different view. They want a better rail service in (say) Manchester, because Manchester is competing for inward investment with the likes of Dusseldorf. It is a very different mindset.The northern economy is changing. There is less work in factories and more work in city centres by people wearing suits. And that means we commute more.

“Clearly the DfT had to take the huge response to last year’s consultation on board. An approaching General Election also affected the franchise specification - George Osborne and Patrick McLoughlin wanted something positive and upbeat. Rail North wanted full devolution of both franchises. DfT said no, but went for a partnership agreement between them.

“I think in five years’ time the Northern product will have been transformed, because the specification for the next franchise is transformational. And that is partly because it has been influenced by Rail North’s involvement in the process.”

Rail devolution in other regions

Could rail devolution work elsewhere in the UK?

“I think it could,” says Merseytravel’s Brown. “We have a big geography, a high level of subsidy, and an historic lack of investment, so we have taken on perhaps the biggest challenge. The evidence to support it is here. The trains in Liverpool used to be called Miseryrail - they were the worst in the country for performance. Now they are among the best.”

Meanwhile, Northern Rail’s Hynes comments: “A local focus does bring local benefits. My instinct tells me the more Rail North control, the more money they will want to spend on it. At the moment, in-franchise change is such bloody hard work. In the future it will be easier to get good stuff done.

“Look at what LOROL did in London. It got the franchise, then Transport for London said it wanted to lengthen trains and improve stations. LOROL has done a great job because London was prepared to pay more for what used to be Silverlink Metro than central government thought was justified. For the DfT, Silverlink Metro was not part of its agenda. But London saw in it an opportunity to reduce congestion on the Tube and a chance to make poor areas richer. And they spent shed-loads of money on it.”

Mike Brown, managing director of rail and Underground for Transport for London, explains: “Our model of devolution is not a one-off for London. The differential lies between middle-distance routes and what you might call urban or suburban rail. In our model there is a recognition that revenue generation and ridership is a macro-economic factor, and not one that is at the disposal of any one operator to influence. Yes, they can do a bit at the margins - off-peak and weekends - but generally speaking, in big conurbations people use railways because they don’t have any viable alternative.