It is rail regulator the Office of Rail and Road that must choose between them. But it faces a very difficult task. Open access operators are popular with passengers and score well in passenger surveys. They often offer direct services to destinations not served (or not served well) by franchised operators.

On the other hand, ORR must also consider the financial position of ministers and VTEC’s £3.3bn is hard to ignore in this context. ORR runs prospective open access bids through a test that determines whether those bids are ‘primarily abstractive’ - in other words, do they simply take too much money from existing services and passengers, rather than generating genuinely new custom to rail. Hence the emphasis placed on the air market by the two Edinburgh bids.

And while other services may run to stations not currently served by direct London trains, they could still be abstractive on a section of the ECML itself. For instance, London-Yorkshire could take revenue on the leg from the capital to Doncaster.

The ability of open access operators to run is enshrined in the legislation that privatised British Rail back in the 1990s. It provides for licences to be granted to non-franchised passenger operators, and allows them to enter into track access contracts with Network Rail if approved by the regulator. Open access operators are charged marginal access rates on the basis that they only incur marginal costs for Network Rail.

This works if there is spare capacity lying unused. The fact that perhaps another half dozen daily trains run does not add much to NR’s costs - they add little in the way of track wear and tear, and signallers and other staff are being paid for anyway.

But the difficulty comes if major upgrades have to be provided to create new capacity. When that happens, it cannot be considered that open access operators are using marginal capacity.

The ECML has already had a series of improvements delivered over the past few years (flyovers at Hitchin and Doncaster, new platforms at Peterborough, layout changes at York and the Finsbury Park work mentioned earlier).

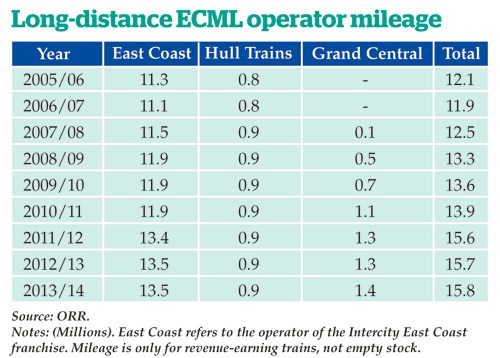

But with capacity still tight, there is more to come, paid for from NR’s East Coast Connectivity Fund. This fund is £247 million over the five years of Control Period 5 (2014-19). Meanwhile, the company’s income from all open access passenger operators (which also includes Heathrow Express) in 2013/14 was just £24m.

It’s always difficult to split the money that government provides to subsidise non-commercial franchised services and the money that it provides directly to NR down to line and route level. However, ORR provides an annual financial report that attempts to shine some light on this complex world of railway financing. The latest report covers 2013/14, and shows that government provides just over a quarter of the total revenue for UK rail.

Delving into the figures for East Coast (VTEC’s predecessor) shows that EC’s share of NR’s government grant was £194m, while EC paid government £217m in premium payments. On this basis, there was a £23m surplus on government money. (EC also paid NR £117m in access charges in 2013/14).

In cash terms, the forthcoming improvements tip EC figures into annual deficit, but the improvements are enduring and are added to NR’s Regulatory Asset Base, on which the company is allowed to earn a return over a considerably longer period. But whichever accounting treatment is used, NR’s open access annual income of £24m (albeit it will rise if more services run) compares badly with the Government’s £3.3bn premium over eight years (which starts at £212m in 2015/16 and rises to £645m in 2022/23).

The presence of such substantial sums of money skews the argument in favour of the Government’s franchisee and away from services that have a demonstrably popular passenger record. Research also suggests that the presence of competition on the ECML route has kept franchised fares in check, boosting the benefits that open access provides but also blunting the return that government could (and expects to) generate.

North of Newcastle

And it’s not just the London end of the line that generates tricky capacity decisions. The ECML north from Newcastle is twin-track. In its December 2014 capacity report, Network Rail was only confident in suggesting that there were three hourly paths available to long-distance services, and suggested a split between two London trains and one from elsewhere - either a CrossCountry (XC) or an inter-regional service, which could have originated from a trans-Pennine corridor.

With VTEC having already staked a claim to two London services, this might have raised a difficult decision for the third path. Some clarity of the Government’s intentions come with its tender document for TransPennine Express, which makes no mention of TPE services extending north of Newcastle.

With First and Alliance in the mix, ORR faces a decision over giving all capacity north of Newcastle to trains serving London, and thus cutting XC from Scotland. This should be possible with through ticketing, even with Advance Purchase tickets, allowing passengers to change from XC at Newcastle onto other trains. However, this flies in the face of passenger preferences to change as few times as possible.

That said, East Coast’s 2011 Eureka timetable rewrite introduced a similar concept. For many passengers travelling between stations north and south of York, it enforced a change at York for connecting services to and from intermediate ECML stations such as Newark, Retford and Grantham, allowing Anglo-Scottish trains to run non-stop between York and London. The ‘stopper’ simply ran between London and York, in a construct that could apply to XC services if they were to be cut back at York or Newcastle.

Introducing more open access could also break into the clockface timetables that have been grasped by railway companies in recent years and which are likely to continue to be pushed. However, it might well be worth terminating a few XC services at York or Newcastle to allow one of Alliance’s fast London-Edinburgh trains to run. But how do you decide?!

This is a matter of weighing one set of passenger benefits against another. Speed is valued, but railway operators seem to favour clockface, perhaps for their operational ease - although given the increase in advance purchase tickets, the concept is becoming less relevant for passengers because these tickets tie their holders to specific trains.

That increase is striking. According to the Rail Delivery Group, there was a 9.6% increase in ‘AP’ tickets in 2014, rising from 55.8 million journeys in 2013 to 61.1 million in 2014. Revenue has risen from £0.1bn in 2002 to £1.1bn in 2012. What’s less clear is the extent to which operators have discounted tickets to fill clockface trains running at times when they might not be commercially viable. In other words, using a path because it’s there, rather than because it’s needed.

That would suggest that if other services bring a more commercial prospect, then they should take priority, even at the expense of another operator’s clockface service. Perhaps the fast nine-coach London-Edinburgh filled with those transferring from air generates more revenue than a four-coach service filled with £10 fares. Clearly that example is extremely simplified and exaggerated, but it serves to make a concentrated point.

It also serves to show the degree of second-guessing that goes on in a railway that is neither public nor private. The private operator will make its plans based on revenue predictions to justify whether or not to run trains, but Britain now has a system whereby the ORR has to decide between competing plans from commercial operators and from those running the service the Government wants and thinks it has paid for. ORR referees a railway game, while the real competition comes from cars, coaches and planes.

Clockface timetables are a dated concept in an age of better access to information, particularly via mobile phones. It’s easier now just to check when the next train to your station runs and then catch it, rather than remembering that they run at twenty to and twenty past each hour. The concept of clockface is being implemented just as it becomes obsolete from a passenger perspective.

That said, the concept remains useful for railway companies, particularly as lines become more congested. Their predictable nature is easier to work with and they work well with ‘flighting’ (the concept of setting trains off a few minutes apart depending on stopping pattern - the train with the most stops being last in the flight).

In maximising capacity, timetables drag trains down towards the speed of the slowest, because that’s how you accommodate more services. It works against the fast train that tempts passengers away from aeroplanes and thus grows the rail market, because that fast train absorbs so much route capacity.