“The key thing is that cascaded trains have to be delivered fully refurbished, with everything done. Some people in the North are complaining about getting the South’s rejects to operate beneath the wires between Manchester and Liverpool. But actually we’ve refreshed them - we’ve put audio and visual passenger information in them, and repainted them. My customers will think they are like new. Rolling stock quality is on the political agenda here. That can only be good.”

Burleigh agrees: “There are lots of suburban and inter-regional electric trains coming up. When we transition these to a diesel part of the network, passengers will not want to see trains that fail to match the capability, the comfort and the information provision of newer trains. Lower quality is an inhibitor to future growth. The new trains coming elsewhere lead to higher expectations for other trains, too.”

But he warns of very real affordability constraints: “Electrification costs have gone up. We are dependent on whatever the pace and scale of the future electrification programme will be. It’s still very much in flux.

“There will come a point where the balance of funding between electrification against new rolling stock will have to change, and that may mean we see some of the existing stock retained for longer than anticipated.

“We need to align the fleet with growing expectations - some elderly fleets are unloved and much derided. That’s why there has been a lot of investment in demonstrator trains, to show how a new-train feel can be imparted to existing trains. Several regions will still retain unelectrified routes, and there will be a medium-term need for self-propelled rolling stock. And that currently means diesel.

“We have to look at whole-life assets. We are certainly looking at retractioning some of our existing trains. And while there aren’t current alternatives to diesel propulsion, the automotive sector is moving on apace. So it could happen.

“So when we engage with manufacturers about any future new diesel stock, we are looking for modular designs with the potential to accommodate a future upgrade when those alternatives mature - perhaps in the final quartile of the asset’s lifespan. Look too at the work sponsored by Network Rail on an independently powered electric demonstrator. You could see for some routes that might one day prove attractive.”

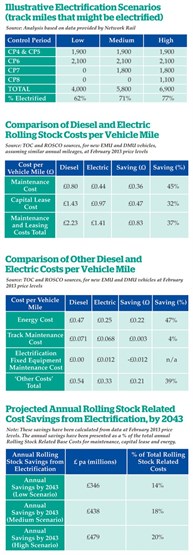

The rolling stock strategy document sets out a substantial projected reduction in costs, resulting from the switch to lower-maintenance electric traction and a stable production rate of units that share common standards.

At 2013 prices, the strategy states that the maintenance cost of a diesel is 80p per mile, compared with 44p for an electric train. Combined with the lower energy and capital lease costs, an electric train works out as 37% cheaper to run.

But in the light of the enormous drop in oil price since summer 2014, the warning in last year’s document was impressively well-timed: “Future energy costs are very difficult to forecast. Diesel fuel costs may in future rise faster than electricity costs, but the reverse is also possible. Electricity costs are currently rising to help pay for lower carbon sources. It is possible that the cost of fossil fuels used in generation may fall from their current high levels.”

So if there is no grand cascade plan… if the control of it lies in many different hands… if the pace and extent of future electrification remains in the hands of a future government that may have other priorities… how can the operational railway prepare for the next round of hand-to-mouth changes?

“There is no rocket science in this,” says Burleigh. “A successful cascade needs a lot of groundwork. It’s not just about the trains - it’s the training of the operators, training of the people who will train the fitters. It’s about having the depots and the stabling ready before the trains arrive.

“Moving from a diesel fleet to an EMU fleet brings practical challenges in terms of off-peak and overnight stables. In many cases this is not a trivial issue - replacing a two-car DMU with a three- or four-car EMU needs longer depot sheds and longer sidings. Large fleets being split means an appropriate allocation of spares, documentation, a different management of overhauls and maintenance schedules.

“And it means making sure the passenger-facing aspects are sorted long before the trains arrive. Has the recipient operator got the passenger information re-programmed? Has it made sure the booking systems reflect the seating layout, and maybe a different split between First and Standard Class than it had before?

“If these things are not done well, they can take a long time to overcome. Short-term issues and pressures can lead to some of these vital steps being rushed or omitted. Constantly moving fleets around is not a recipe for best performance.

“If you’re looking for long-term stability, the compatibility of the mix of rolling stock is key - stopping and inter-regional services have to work well alongside each other, especially if they share a depot. What happens with the electric suburban fleet running alongside IEP will be a good example.

“The franchise competition for Northern is now running. We’re the smallest rolling stock provider to Northern - we’ve invested in the incumbent fleet of ‘321s’ and ‘322s’. With our demonstrator we’ve created a new-train environment, and we are in discussions with anyone who may be interested. New trains may not be affordable there. There mustn’t be a perception about the North getting cast-offs. Quality is now a higher proportion of the DfT’s overall evaluation of bids.”

Burleigh points to the way Transport Scotland handled the recent ScotRail franchise (Abellio takes over from FirstGroup on April 1).

“We saw from Transport Scotland a very high requirement that any train moving across needs a good-quality interior, it needs to meet accessibility requirements, and it needs to be in the correct livery before it moves. All that was published in the Invitation To Tender.

“It spelled out by service groups the minimum functionality needed in terms of WiFi, power points, tables and air-conditioning. That was immensely helpful to us. There was a very comprehensive stakeholder consultation. It shared a draft ITT with all potential bidders and suppliers. That gave us an early chance to come up with more mature proposals.

“For example, when extra facilities are sought, the obvious thing to do is to combine that work with the existing heavy maintenance cycle - when the trains are out of service, anyway. The bigger fleets take three or four years to work through a heavy maintenance programme and you don’t want to take them out twice - the work needs to be done together so the trains can stay with the operator earning money.”

So is Transport Scotland’s refranchising a model for the Department for Transport to follow?

“It could be the model for the rest of the industry. We do know there has been dialogue. We really welcome it - it’s very helpful to us. We are keen to get early visibility of what the franchise objectives are going to be, so we can talk to our supply chain to commit to the pricing well before we deliver any enhancements, especially when they are needed very early in the franchise.

“From the Department for Transport perspective, it is beginning to work through into a more consistent system. There is a will to get into a more consultative regime where ourselves and others can influence the shape of future franchises.

“The franchising is becoming a two-year cycle. The first year is about consultation, so they get right what they want to buy before they embark on the competition phase.

“The bidders get a 120-day response time. But in that you have to take chunks off for scrutiny, review and approvals. If you’re not careful, bidders get very limited time to work up technical details and the pricing of fleet enhancements. That’s why we put a lot of effort into engaging with stakeholders even before an ITT is around in draft form.”

Third rail to overhead wires

In the current debate about how far and how fast electrification can proceed, Network Rail is evaluating the consequences of replacing the third rail DC system with overhead wires, although the sheer number of route miles and the intensity of operation means this is likely to become a longer-term goal.

Eversholt, which owns Southern’s huge fleet of Derby-built Electrostars, recognises clear benefits in terms of efficiency, resilience and capacity. But it warns that the practical challenges and costs of implementation are likely to push this down the agenda.

Getting from one state to the other (DC to AC current) may mean dual-voltage EMUs or modification of existing trains. The Electrostars were designed with conversion to AC built in, with space for pantographs and provision for running power cables through the carriages.

“Inevitably an operator’s horizon is only a few years long,” says Burleigh. “But we have to consider from the outset what we might need in the final years of that asset’s life. Dual-voltage operation clearly figured in that. The viability and commercial attractiveness of AC conversion will depend on how far ahead that decision is made. We’re not expecting it in the short term!”

It is now six years since anyone placed an order for a DMU. In that time, none of the old ones (however unloved) have been pensioned off because passengers need them.

Although electric trains are cheaper to operate, those lower bills alone do not offset the capital cost of electrification. The business case for putting up wires is a combination of cost reductions and the increased revenue that flows from more passengers attracted to modern trains (with the greater capacity they can offer and the wider socio-economic benefits that are so notoriously difficult to quantify, but which are widely accepted).

The industry says we need up to 19,000 electric vehicles over 30 years, but only 100 diesel units by 2043. No wonder the Rolling Stock Strategy says it is “probable there will be a business case” for further extending the life of diesel stock built under British Rail. It further states: “No new diesel vehicles would be required to be built in either CP5 or CP6.” So nothing until the 2020s. Though it predicts that up to half the old British Rail DMUs will be scrapped by 2024, it is likely that some old diesel trains – including HSTs - will still be in daily service when they are more than fifty years old. The motoring equivalent is what? An Austin Allegro? A Ford Cortina would be positively modern in comparison. This is a situation unthinkable in the car, bus or aviation industries.

The strategy estimates that a 50% increase in berthing capacity will be needed. Those old sidings have a future, while new depots will be required - especially in the West, North West and in Scotland, where demand for regional services is expected to rise faster than elsewhere.

And yet there is no formal plan for a cascade of rolling stock to fit this truly remarkable, unprecedented and geographically uneven growth scenario. The Government believes that the market will provide what the customer demands.

But today there is a shortage of rolling stock. DMUs are at a premium - there aren’t enough of them, and the wires are not yet ready to take the flow of second-hand electric services that will flow three years from now.

“I don’t see any evidence that DfT has acknowledged there is a problem,” says our senior rail industry executive. “It does not see that the solution lies at the centre. But that is the inevitable conclusion to get around the grief and cost that will follow.

“They’ve created a rail executive within the Department, under Peter Wilkinson and Claire Moriarty. There’s talk of spinning that out after a General Election and making it into an arrangement like the Highways Agency. The SRA got too big for it boots. But the HA is not too big for its boots - it’s just a centre of expertise. That’s what the Department for Transport desperately needs.

“It screwed up West Coast because the railways were being run by people who knew nothing about railways. That’s being corrected. The state getting involved is not something I would normally welcome, but in Wilkinson’s position I would take control, and be more centrally planned and interventionist about the cascade. The Department needs a joined-up long-term plan for rolling stock. Because currently it doesn’t exist.”