Smartcards offer a solution, according to Hewitson at Passenger Focus. “When you click in and click out, the system knows whose train you are on, where and at what time, and sends all the money to that operator,” he says. “That could lead to companies competing for customers on the basis of good service, clean toilets, no rubbish on the seats, or a loyalty reward for regular travellers.”

The evolution of smartcards on the railway is far behind the bus industry… and far behind the expectations of passengers, politicians and operators alike.

“The South East Fast Ticketing Initiative (SEFT) has been so slow,” complains CBT’s Joseph. “The Department has spent years not delivering it. Government doesn’t like taking leads on IT initiatives - its record is pretty terrible.”

SEFT was set up in 2011 with £45 million of Government money, much of which remains unspent. Across most of the capital, commuters still get nothing more than a paper season ticket with a magnetic stripe, which often fails within a few weeks - leaving premium customers queuing slowly at the manual ticket gate, the last to leave the platform.

“Oyster came in because a few key people had a vision and made it happen,” says Hewitson. “Smartcards did not have the same grip, the same dynamic leadership. It was held up by 20 train companies, sitting around a table wondering what to do.

“If you have a ten-year franchise, it takes most of that time to set up a smartcard system and costs a lot. So unless the Government writes it in as a franchise commitment, it’s not going to happen - there simply isn’t enough payback time.”

Passenger Focus thinks national rail travellers will take longer to trust a plastic card system than Tube travellers did with Oyster. If you’re commuting for an hour, will you accept that a simple tap in and tap out has charged the right amount? With Oyster the cost of getting a fare wrong is only a few pounds; on a main line railway it could turn the bank balance red.

Yet smartcards could also bring a range of payments for a part-time commuter - those who travel three days a week could see a real benefit.

“We’ve been talking with Government about flexible part-time ticketing,” says Joseph. “They’ve found this very difficult. We were told there would be smart carnet tickets across the South East. Then some of the train operators objected and the idea has gone backwards. I think the Government would have to compensate train operators, even though we all know smart ticketing will quickly drive more business their way. The Government finds that a hard sell.”

“Smart tickets will also enable Rail Miles,” adds Hewitson. “Air Miles work really well as a reward system. They could lead to a free cup of coffee every so often - this could mark the shift from being a simple utility provider, moving a person from being a passenger to a customer. You can do the occasional freebie if the operator knows who you are, where you travel and how often.”

Steer believes smart ticketing will bring massive savings for the industry. In particular, he points to the ability to get new organisations selling tickets - with fares reform, they would not have to engage with the complexities of the current system.

“The holy grail with smart ticketing is tailoring products to individual customers,” he argues. “They can find the person who wants to travel First Class, paying extra for premium car parking. You could also offer free or deeply discounted travel for people going to job interviews - these things are much easier if you are overlaying them on a simpler fares structure. The social value approach to fares goes hand in hand with a simpler system.

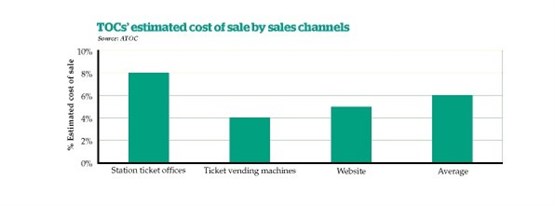

“It needs a Government which will reduce the cost of retailing. We could take 5% out of the cost of running the railway - all the companies want to close ticket offices. But as things stand they can’t. We need to remove a very inefficient and archaic system.”

Go-Ahead Group’s Southern Railway has taken the lead here. Since the autumn, it has been possible to get on a bus in Brighton, then the train to London, onto the Tube, and to finally catch another bus - all on the same piece of plastic. It works from Bognor Regis to Bethnal Green, or from Eastbourne to Ealing Broadway.

For that to happen, 20,000 gates and readers have been updated, led by Cubic Transportation Systems. Riz Wahid, head of retail at Go-Ahead, has worked on the project since 2009.

“KeyGo is the next step: our version of pay-as-you-go. It’s currently working outside London. I’m in discussions with Transport for London to get our version working inside the capital as well.

“As you register your Key, you also register a bank card against your account. So if you tap in at Brighton and tap out at Lewes, we look at the route you’ve travelled, any entitlements you may have, at Singles and Returns, and all the tap data. This enables us to charge for the cheapest journey you made at that time.”

That requires a 100% reliable system that the passenger can trust, and the low take-up of The Key (the smartcard system of which KeyGo is part) suggests it isn’t there yet - currently only 250 customers use KeyGo in Brighton and Crawley. Changing passengers’ habits (Wahid calls it “migrating them over”) is not happening fast.

“I have a team of engagement managers working on it,” he says. “What we don’t have is a price difference between paper and plastic. The fares are the same. We need to make offers that are plastic-only to bring change. That’s something we’re working on with DfT, but it means changing fares regulation.”

“Go-Ahead’s efforts deserves credit, says Joseph. “It put the work in, to make The Key interact with Oyster. Go-Ahead did not strictly have to do that. I’ve been told by National Express that the work done by Go-Ahead greatly eases their task on Essex Thameside. Go-Ahead went through hundreds of iterations to iron out bugs in the system - so others won’t need to.”

Essex Thameside is planning to run its own smartcards, but in principle The Key could work outside the Go-Ahead franchises. Wahid says a franchise extension on Southeastern will include a commitment to extend The Key into Kent. It will also appear on the new Thameslink concession.

“There is no reason why we couldn’t agree with people like Stagecoach for our card to be accepted on their network,” he says. “They would get the same revenue as they would from a paper ticket. So there is no revenue risk to train operators at all.

“We just have to make sure those train companies have a device that works our cards. We had to do the work with TfL to make sure that if a customer turns up at (say) Islington with one of our cards, the staff there have a device that can read it - even if the staff have never seen The Key before.

“Technically that is relatively straightforward. It’s more about the commercial agreements and the training.”

But if others go their own way, such as Essex Thameside, won’t an already absurd variety of fares and ways to pay for them become insufferable? Wahid says he has given SEFT the Go-Ahead technology.

“There’s nothing stopping another operator coming up with its own version, but it would get very difficult, very confusing for the customer if we all have our own versions of the same thing.”

But why use a dedicated charge card? Surely a contactless bank card, which can be read throughout London, can do the same job. One card fits all?

TfL thinks it heralds a likely change in the way millions of Tube users pay for their journeys. But it won’t help children without bank accounts heading to school - there are many people for whom a plastic card such as The Key will remain essential if paper tickets are replaced.

Wahid concludes: “In a few years, I hope we will remove the complexities of customers going to self-service machines every day and remove the queues at ticket offices. We need customers to touch in, touch out, whatever their journey.”

So where does that leave us? More than 713 million passenger journeys were made in the six months to September 2014 - that’s a 3.7% increase on the same period last year, equivalent to more than 140,000 additional passengers a day, according to the Rail Delivery Group. The growth outstrips other European countries, with passenger numbers rising by 62% in the UK between 1997-98 and 2010-11. That compares with 33% in France, 16% in Germany and 6% in the Netherlands.

Does it all really matter?

So the increasing complexity of fares has arguably had no ill effect, despite our ticketing structure being a good deal less easy to understand than that of our European neighbours.

Our travel by train also costs more - from January the annual season ticket is expected to rise on average by 2.5%, which is nearly six times the average rise in wages.

The industry is confident passenger numbers will still grow… and keep on growing for the foreseeable future. Why bother with the costly complication and sheer hassle of developing a different fares structure if the existing one will keep the cash rolling in? There is no incentive to change.

This frankly ludicrous system works. Not efficiently. Not smoothly. Not cheaply.

Split ticketing has no place in a well-organised railway, because it serves no purpose.

A single fare that costs £1 less than a return fare makes no sense in a smartcard future.

And the paper ticket already abolished by airlines is an anachronism. Yet it is likely to continue for many years to come - quaint and perhaps quintessentially British, like wearing tweed in the rain in preference to the latest waterproof fabric.

But what if the fares system could be rebuilt as well? Everybody interviewed for this article thinks it should change. Almost everybody interviewed also thinks it won’t change.

Yet ATOC’s comments here are genuinely new. The train operators themselves are open to the idea of sweeping away the regulated Off Peak Return and having airline-style single-leg journeys instead. The Department for Transport will organise a trial. The barriers to change have not yet been removed, but they are no longer padlocked in place.

Nobody designing a new fares structure would come up with anything close to what we have today. In the fragmented passenger railway, there are 20 different pricing managers inevitably seeking to manipulate the system in 20 different ways. But fares regulation keeps things together - more or less.

But because passenger numbers will continue to grow regardless, there are many reasons not to pick what almost everyone thinks is The Right Thing To Do: tear up the system and start again.