Today, there are varieties of tickets on smartcards, mobile phones, third-party websites, sent by post, or collected from competing operators’ ticket machines at the same station. We have complicated the act of purchase, as well as making the tickets themselves bewildering.

“If you ask people whether they want more choice, they will say yes,” says Hewitson. “If you ask them whether they want a simpler system that is easy to use, they will say yes to that as well. How do you square that circle?”

There are now three generic types of ticket: Anytime, Off-Peak and Advance. Every operator uses the same terminology.

On long-distance travel, the Off-Peak fare is regulated. Peak fares are unregulated. People generally make these journeys relatively seldom - the typical inter-city passenger makes a handful of premeditated journeys a year.

On short-distance travel, the Peak fare is regulated. Off-Peak fares are unregulated. Travellers make shorter journeys relatively often - every day, every week, every month. They often travel at short notice, expecting flexibility in ticketing.

Barry Doe, RAIL’s timetabling and fares expert, says that the current problems stem from the 1993 legislation’s decision to cap Off-Peak fares

“The train operators had to look at ways to improve their Off-Peak opportunity - the lion’s share of their revenue in most cases. So they abolished anything that was cheaper than the standard Off-Peak. But they were all tied into ORCATS. So whatever ticket was sold, each train operator was going to lose some of that revenue. Whatever Virgin took between London and Glasgow, 20% to 30% of it went to East Coast. And vice-versa.

“The only way out of that loss was to offer operator-specific fares. The train operator could offer a lower fare, but from which it could keep the entire revenue.”

Fares overload

The result: between London and Birmingham, there are, incredibly, now around 100 fares. Even on the 30-mile journey between Gatwick Airport and London there are 15 different single fares and this is impossibly confusing for first-time visitors to Britain.

“It doesn’t really offer the public anything useful,” says Doe. “It’s about pushing revenue the way of one particular operator. It’s just playing the system, perfectly legally. Plenty of booking clerks struggle to understand how it works.”

When the wide variety of Advance fares is added, Virgin has about ten different options between any two stations. That’s ten Standard, and ten First. The cheapest fare between London and Manchester is around £10 Single, rising to well over £200.

“If you turn up at a ticket machine, you can get dozens of options, all set out in railway jargon - a big mistake,” says Doe.

“And it isn’t in simple English either. For example, it assumes everyone knows what ‘Route not London’ means. If you did Salisbury to Brighton, would you guess that ‘Route not London’ means you could still do Salisbury to Clapham Junction and down? Of course you wouldn’t.”

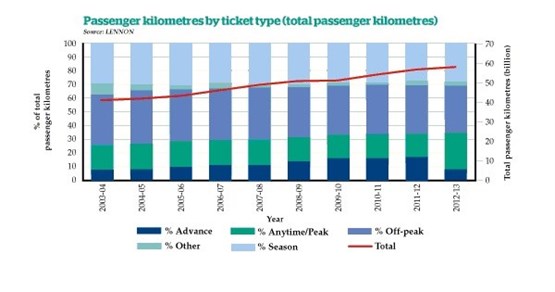

Advance fares make up a small proportion of the total. Most people still either buy season tickets or ‘turn up and go’ - nationally 50% are season tickets, 47% are walk-on fares and 3% are Advance. However, Doe says that on some trains from Euston perhaps half the tickets may be Advance, whereas from Woking to Waterloo there are none at all.

ATOC’s Mapp defends the way the system works: “We’ve actually had a common national fares structure since 2008. We have Advance, Super Off Peak, Off Peak and Anytime on long-distance; Off Peak and Anytime on short-distance. The Advance fares - the operator-specific fares - still conform to a common standard. We have pulled off a difficult balancing act - a consistent fare structure providing some opportunity for operators to set fares specific to their services.”

But is this good for business? Stephen Joseph, executive director of the Campaign for Better Transport, says: “If you are a national business - say the BBC or Sky - and you have offices all over the place, you get treated really badly by the railway. You have to negotiate with individual train operators for individual deals. You’re not given any frequent-user benefits. There are no discounts.

“Major businesses with corporate social responsibility policies want to use rail rather than road. But they find it very difficult. The railway is throwing away good business.”

Adds Doe: “Virgin came along with new Pendolinos - a massive investment - and was unable to put up its Off Peak fares to recoup the money. Off Peak fares must remain for evermore at the 1995 level plus whatever capped increase is permitted each year. Crazy commercially, but those are the rules.

“So with the Off Peak capped, the companies have all pushed up the Single peak fares - the only way they can charge the business account traveller. That’s why we’ve seen a 250% increase since privatisation - even accounting for inflation, that’s a doubling.

“It is a direct result of capping the wrong fares. They should have capped the most expensive fares.”

The result is confounding. The cheapest Advance fare from London to Manchester works out at 6p a mile. In the peak it rises to 87p a mile in Standard, 125p a mile in First.

Weymouth and Taunton are equal distance from London. Weymouth in the peak costs 42p a mile, Taunton is 79p. Yet South West Trains, despite charging almost half the price per mile, offers more frequent services on newer trains.

Meanwhile, the cost of putting petrol in the family car is around 13p a mile. Even adding in all the other motoring costs, for the majority of journeys, going by road is cheaper than a walk-on long-distance rail fare.

“The industry goes at the pace of the slowest,” says Joseph. “To get any change across the network, all the train operators have to sign up for it. Their incentive is always to do operator-specific ticketing because the operator sees more of the revenue. So the incentive is always to preserve - and further complicate - the system. The result is that fairness often plays no part in the pricing structure.

“Only the Government can take a view on this, because only the Government holds the total profit-and-loss account. If you wanted to buy out the system oddities, some operators would lose out. The losers would shout loudly. So nobody picks up on the benefits of simplification driving growth.”

Rip it up and start again?

“There has been no serious attempt to modernise the way fares are levied in this country since the 1980s,” says Jim Steer.

“The system is far behind today’s needs. The complexity acts as a deterrent to using rail. It loses a huge proportion of people and therefore loses revenue.”

Mark Smith, otherwise known as online consultant The Man in Seat 61, says: “The really major fly in the ointment is that Off Peak Returns are only £1 more than the equivalent Single. This idea was inherited from British Rail at a time when it made sense commercially. It is now fossilised by fares regulation. The Off Peak Return is regulated, so it cannot be increased. And the Off Peak Single cannot be decreased without significant revenue loss.”

Doe agrees: “The first thing I’d do is abolish long-distance Returns. We need a structure where a Single is the only fare you can get. Not today’s Singles, but half today’s Returns. So you’d get a cheap early Single, a higher Single in the peak, a lower Single again after 1000. How easy would it be then? You get the fare on the machine relevant to the time of day.”

But here’s the element of surprise… the Association of Train Operating Companies agrees (more or less) with all of that.

Mapp acknowledges: “Reform is a viable option. Potentially having only Single fares on long-distance, allowing passengers to mix and match to suit their own travel needs, is an interesting way forward. It is simpler to understand and provides greater flexibility. On short-distance we are likely to continue with Return for the foreseeable future because there is strong demand.”

Smith gives an example of why the current system confuses passengers. “You make a journey on a Friday, coming back on Sunday. A decision to use an Off Peak on your Sunday night return, because you don’t know exactly what time you will be coming back, not only affects your choice of fare on the Friday outward leg (you might as well pay the extra £1 and get an Off Peak Return), but also your choice of train.

Reform and revenue implications

“You now have to shift your departure to the 1900 train (the first Off Peak departure after the Peak), rather than the 1700 or 1800 you actually wanted, even if cheap Advance fares are available on them. That explains why the 1900 goes out loaded to the gunwales, while the 1700 and 1800 go out with lots of empty seats.

Doe warns: “Reform has huge revenue implications. A Single from Andover to London is only £2 cheaper than the Return Off Peak. Which is obviously daft.

“South West Trains tells me it couldn’t just be half today’s Return, it would have to be slightly higher. But at least then everybody could mix and match. You would simply pay the appropriate fare on the way back. It would be a lot more flexible.”

Steer thinks a zonal structure is worth considering. He recalls the Ken Livingstone-era GLC in London, when London Transport went to a two-zone system.

“This was the birth of the Travelcard,” he says. “Underground and rail, and later bus. The increase in use of public transport was massive. Delivered partly by simplicity and partly by not paying every time you got on and off.”

Mapp is less supportive of the idea, while not dismissing it out of hand: “What Jim suggests is there already in London. It is not a complete solution, but it might make long-distance fares less complex. There is merit in further consideration.

“At the moment we have to offer a through fare from every station to every other station. And the mechanisms we have to do that are quite complicated. Some form of zonal pricing, or hub-and-spoke pricing, might simplify that.”

So if everyone favours scrapping Return fares in favour of Singles only (and we haven’t identified a single dissenter), can it happen?

Doe gives the short answer: “No. The current legislation would prevent it. Ministers want it, but how do you do it? The law enshrines the current practice, capped at today’s levels.”

“The Department for Transport will not relax fares regulation to get rid of this anomaly, as the media would portray it as a sell-out,” believes Smith.

“But if it could be solved, in theory you would get just three choices outbound and three choices back, which could then be clearly and unambiguously displayed online: Anytime, Off-Peak and Advance on each specific train.

“At the moment we are handing passengers a quadratic equation to solve every time they travel. The DfT needs to bite the bullet. It needs to throw some extra subsidy at this.”

“I think the Department for Transport wants change,” suggests PF’s Hewitson. “It did a consultation last year. But if it loses them money the train operators won’t want it, unless the Government underwrites it.”

The DfT declined our interview request. Instead, a spokesman offered a statement: “We recognise passengers are concerned about the cost and complexity of fares. Following a ticketing review in 2013 we set out our vision for simplifying the process. This includes removing the fares flex for 2015. We will also run a trial with a scheme to regulate long-distance Off Peak single tickets, and remove the confusing situation where some single tickets cost nearly as much as return tickets.”

A train operator to conduct the trial during 2015 has been chosen, but at the time of writing has not been announced. ATOC’s Mapp is strongly supportive, but warns: “Ripping up the system is not something you can achieve easily - it means significant change to industry systems and retailing practices, with financial implications for Government.

“But if you are suggesting that some elements of rail pricing that have remained untouched since privatisation now need to be reconsidered, I think we would support that. We would not jump to the conclusion that everything has to be torn up. But if you suggest a more fundamental review is needed, we would not be unsupportive.”