The work in Devon and Cornwall, and further local initiatives such as emerging volunteer-based ‘station adoption’ groups, led to a piece of research called New Futures for Rural Rail, produced against a backdrop of growing concern for the future of rural railways, as privatisation loomed.

The project was funded by BR’s Regional Railways, the Countryside Commission and the Rural Development Commission, and carried out by Transnet (a London research institute). Interestingly, many of the players involved in that project are still very much involved in community rail today, although in widely differing roles.

The report was launched at a conference in the National Railway Museum in September 1992, and advocated two complementary approaches to lightly used rural railways.

For the short term, it proposed setting up Community Rail Partnerships as bottom-up alliances involving local authorities, community groups, small businesses and the rail industry. For the longer term, it advocated ‘micro-franchising’ based on continental models of independent management of local railways.

Getting these ideas put into practice was slow, although the Penistone Line Partnership was formed (on a wing and a prayer, and with a startup budget of about £3) the following year.

It was the success of the PLP, with its music trains, guided walks and quirky events, that got people thinking about community rail. Local authorities across the country expressed interest, and gradually ‘the movement’ took shape. Train operators were slower to come on board, but companies as diverse as Wessex Trains, Arriva Trains Northern and Anglia championed the cause.

The results softened the hearts of the most commercially focused managers: rising passenger numbers, reduced vandalism at stations, and the sort of positive PR that most railway marketeers could only dream of. Community rail wasn’t ‘fluffy’ - it made a positive contribution to the bottom line. But it also contributed to community cohesion and well being, with stations becoming (as they had originally been) focal points of local communities.

By 1997, enough CRPs were in existence to federate together as the Association of Community Rail Partnerships (ACoRP), with a modest base in Huddersfield. While the CRP concept proved a success, micro-franchising as originally perceived never took off, largely owing to the complexity of the UK rail industry and the increasing levels of risk that operators are required to shoulder.

However, the approach of focused local management along a particular route or small network - the ‘community business unit’ - may yet succeed where more ambitious approaches have failed.

Development strategy

The initial success of community rail wasn’t lost on national government. The Strategic Rail Authority built on its achievements, and in November 2004 published its Community Rail Development Strategy, which identified lines that could be ‘designated’ as community rail routes, based on simple and flexible criteria.

These included: relatively low speed (less than 75mph); single or double track (not multiple track); one passenger train operator providing the bulk of services; not directly serving the major conurbations with commuter services; no major freight flows; and not part of the European TENs network.

The Strategy originally had three aims: increasing ridership, freight use and net revenue; managing costs down; greater involvement of the local community. Subsequently, a fourth objective of “promoting economic and social regeneration” was added.

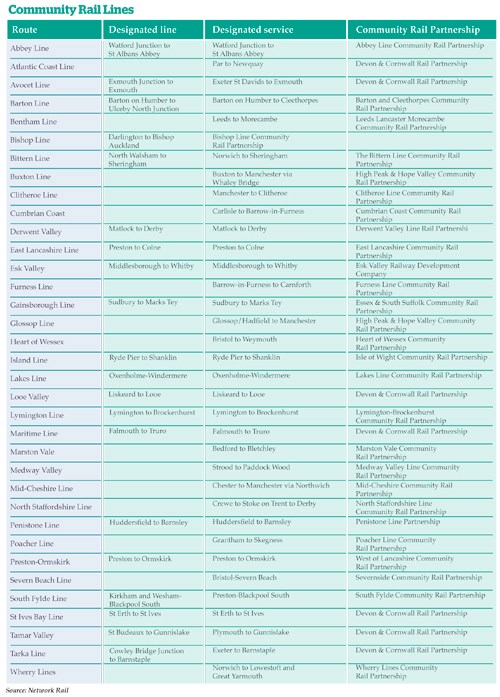

The SRA set up a small but effective community rail team that transferred to the DfT when the SRA was abolished. By 2015, some 39 routes have been designated - either for ‘full route designation’ (which includes infrastructure) or ‘service only’ designation (which primarily relates to commercial activities, including train services and stations). It should be stressed that CRPs can also thrive on ‘non-designated’ lines, including some southeast commuter routes.

Most of the 50-something CRPs feature paid officers supporting a wider network of volunteers. At the same time, the ‘community rail’ concept embraces the hundreds of station friends and station adoption groups that thrive across the national network, bringing an entirely voluntary input to making stations look welcoming and attractive.

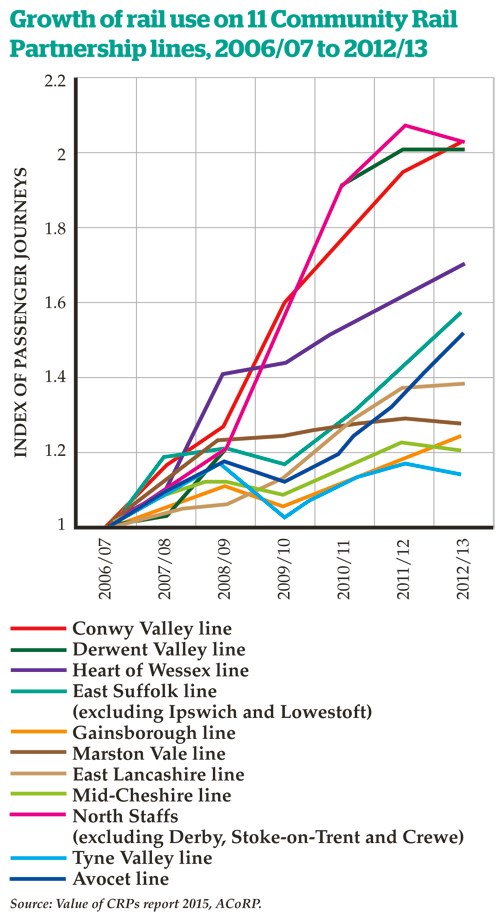

The value of community rail has been demonstrated by a number of DfT-sponsored research projects. The most recent piece of work - The Value of Community Rail Partnerships - updates an original report of 2008, and was published by ACoRP in 2015.