Read the peer reviews for this feature.

Read the peer reviews for this feature.

Download the graphs for this feature.

The British public has spoken and we know where we are for the next five years, in political terms. The new Conservative majority government is likely to continue its existing policies, which have been broadly supportive of rail. Scotland and Wales have their own elections next year, but the positive approach towards rail development, from their respectively SNP and Labour-led governments, is likely to continue.

But what of ‘community rail’, which mainly (but not exclusively) covers those routes that are subsidy-dependent and which have in the past been subject to closure attempts? The numbers are significant and far from marginal. Community rail lines and services are a significant part of the national network, accounting for around 40 million journeys per year. Will there be a renewed threat to their existence, as the Government tries to deliver its £30 billion-worth of cuts?

The Department for Transport will certainly have to shoulder its share of the burden, but there are strong grounds to hope that community rail routes and services will escape unscathed. They are a success story, with rising passenger numbers, with rail making a real contribution to local economies and communities.

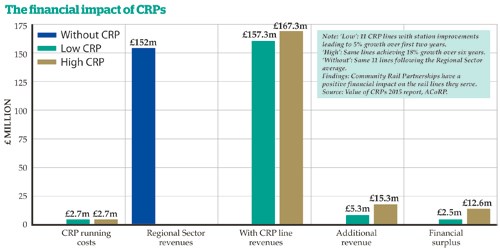

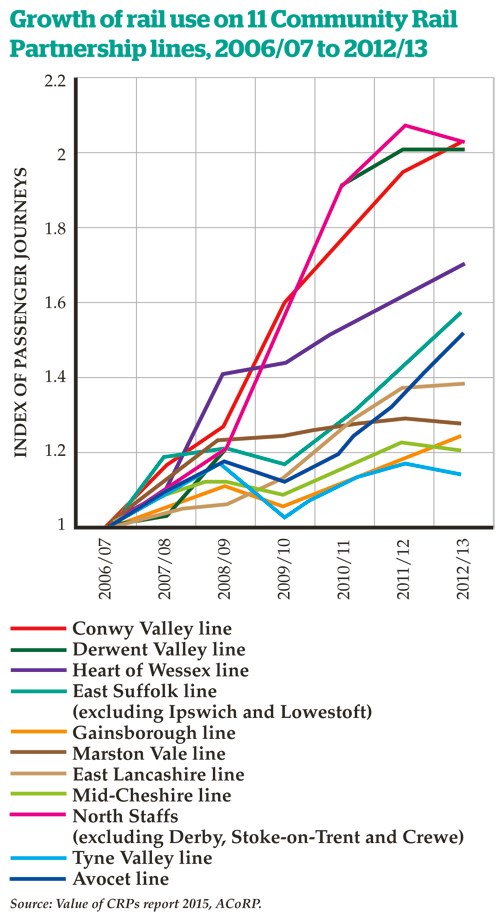

Research has shown that Community Rail Partnerships (CRPs) more than pay for themselves, adding economic, social and environmental value to the communities they serve. They operate in deprived inner-urban areas as well as more remote rural communities with a high dependence on their local rail service. And passenger use on community rail lines has grown by nearly 3% a year on top of the ‘normal’ growth on non-CRP lines.

So why risk a public outcry in this politically sensitive area, knowing that any savings from line closures or service reductions would be a drop in the ocean of rail subsidy? In all likelihood, community railways are safe for the foreseeable future. But the question is: how can they now go forward and improve yet further on the success of the past 20 years?

The evolution of community rail

Many of the best ideas are developed in pubs. Huddersfield’s Head of Steam could be said to be the spiritual home of community rail - it was here, back in the early 1990s, where pints of Yorkshire beer stimulated discussion on how to develop local railways in slightly unconventional ways (such as the hugely successful music trains on the Penistone Line).

And it was in the Head of Steam ten years later, in 2004, that former railways minister Tony McNulty launched the Government’s Community Rail Development Strategy.

In the intervening decade, ‘community rail’ had grown from a good idea into a well-demonstrated means of promoting the greater use and relevance of local railways up and down the country, mostly in England and Wales.

The first CRP was the Devon & Cornwall Rail Initiative (now Partnership), formed in the early 1990s and involving a partnership of local authorities, BR and the University of Plymouth to promote the network of local branch lines in the South West. It has maintained its role as one of the pre-eminent rail development partnerships in the UK, extending its operations to most routes in the region.

The work in Devon and Cornwall, and further local initiatives such as emerging volunteer-based ‘station adoption’ groups, led to a piece of research called New Futures for Rural Rail, produced against a backdrop of growing concern for the future of rural railways, as privatisation loomed.

The project was funded by BR’s Regional Railways, the Countryside Commission and the Rural Development Commission, and carried out by Transnet (a London research institute). Interestingly, many of the players involved in that project are still very much involved in community rail today, although in widely differing roles.

The report was launched at a conference in the National Railway Museum in September 1992, and advocated two complementary approaches to lightly used rural railways.

For the short term, it proposed setting up Community Rail Partnerships as bottom-up alliances involving local authorities, community groups, small businesses and the rail industry. For the longer term, it advocated ‘micro-franchising’ based on continental models of independent management of local railways.

Getting these ideas put into practice was slow, although the Penistone Line Partnership was formed (on a wing and a prayer, and with a startup budget of about £3) the following year.

It was the success of the PLP, with its music trains, guided walks and quirky events, that got people thinking about community rail. Local authorities across the country expressed interest, and gradually ‘the movement’ took shape. Train operators were slower to come on board, but companies as diverse as Wessex Trains, Arriva Trains Northern and Anglia championed the cause.

The results softened the hearts of the most commercially focused managers: rising passenger numbers, reduced vandalism at stations, and the sort of positive PR that most railway marketeers could only dream of. Community rail wasn’t ‘fluffy’ - it made a positive contribution to the bottom line. But it also contributed to community cohesion and well being, with stations becoming (as they had originally been) focal points of local communities.

By 1997, enough CRPs were in existence to federate together as the Association of Community Rail Partnerships (ACoRP), with a modest base in Huddersfield. While the CRP concept proved a success, micro-franchising as originally perceived never took off, largely owing to the complexity of the UK rail industry and the increasing levels of risk that operators are required to shoulder.

However, the approach of focused local management along a particular route or small network - the ‘community business unit’ - may yet succeed where more ambitious approaches have failed.

Development strategy

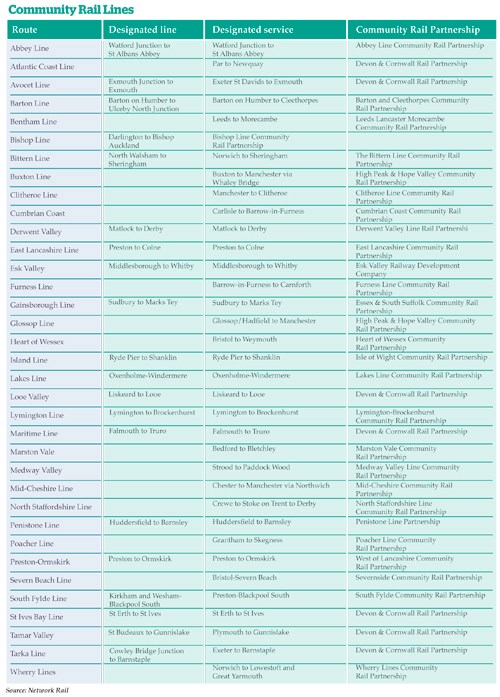

The initial success of community rail wasn’t lost on national government. The Strategic Rail Authority built on its achievements, and in November 2004 published its Community Rail Development Strategy, which identified lines that could be ‘designated’ as community rail routes, based on simple and flexible criteria.

These included: relatively low speed (less than 75mph); single or double track (not multiple track); one passenger train operator providing the bulk of services; not directly serving the major conurbations with commuter services; no major freight flows; and not part of the European TENs network.

The Strategy originally had three aims: increasing ridership, freight use and net revenue; managing costs down; greater involvement of the local community. Subsequently, a fourth objective of “promoting economic and social regeneration” was added.

The SRA set up a small but effective community rail team that transferred to the DfT when the SRA was abolished. By 2015, some 39 routes have been designated - either for ‘full route designation’ (which includes infrastructure) or ‘service only’ designation (which primarily relates to commercial activities, including train services and stations). It should be stressed that CRPs can also thrive on ‘non-designated’ lines, including some southeast commuter routes.

Most of the 50-something CRPs feature paid officers supporting a wider network of volunteers. At the same time, the ‘community rail’ concept embraces the hundreds of station friends and station adoption groups that thrive across the national network, bringing an entirely voluntary input to making stations look welcoming and attractive.

The value of community rail has been demonstrated by a number of DfT-sponsored research projects. The most recent piece of work - The Value of Community Rail Partnerships - updates an original report of 2008, and was published by ACoRP in 2015.

The research found that around 3,200 volunteers contribute 250,000 hours per year (primarily in station adoption activities), providing a financial value of £3.4 million per annum. And it showed that Community Rail Partnerships more than pay for themselves, by adding economic, social and environmental value to their communities.

For example, several CRPs - notably East Lancashire - have an ongoing programme of work with schools that has resulted in growing awareness among children of the value (and excitement) of using their local rail service. Passenger use on community rail lines has grown by an additional 2.8% each year on top of what a ‘conventional’ local line would be expected to achieve.

An honest assessment would say that the Strategy has succeeded in its aims, with the exception of ‘managing costs down’. There is more work to be done.

Stations

Stations act as the link between the railway and the community. The DfT/Rail North specification for the Northern Rail franchise speaks positively about bringing old station buildings back into use, which represents an important change in government thinking.

During the 1970s, hundreds of stations were de-staffed, and many fine buildings were demolished, to be replaced by a humble shelter. Thus the link to the community was effectively severed. But some survived and have experienced a renaissance, often thanks to help from the Railway Heritage Trust.

Gobowen, in Shropshire, is a good example. This once-unstaffed station is now run by a local social enterprise, with friendly and well-trained staff who can sell you a ticket to anywhere from Penzance to Plockton. There is also a nice warm area to sit and wait, with the added attraction of a cafe run by the local school. Gobowen isn’t unique, but it has seldom been easy.

At Moorthorpe, in West Yorkshire, the local town council refused to accept the demolition of the fine (but derelict) station building. It has since been superbly renovated with office space, a cafe and room for passengers to wait for their train in comfort. But this took over a decade to come to fruition, and the building was very nearly reduced to rubble. It shouldn’t have to be so difficult.

Close to Moorthorpe, Wakefield Kirkgate - once dubbed ‘Britain’s worst station’ - is being brought back to life in a £4.5 million project led by Groundwork Trust, in partnership with the railway industry, the local authority and Metro. The new station is due to open by summer 2015, and will be a shining example of what can be achieved with determination and no small measure of luck. The restored station building will house office space for small businesses, a conference venue, a cafe and much-improved passenger facilities.

Several other stations have come back to life thanks to local entrepreneurs deciding to take a risk and provide a good facility for passengers. Chester-le-Street (trading as ‘Chester-le-Track’), its subsidiary at Eaglescliffe and the Lancashire County Council-staffed Carnforth and Clitheroe are all good examples. Settle and Appleby are stations run by and for the local community, through the Settle-Carlisle Development Company working in partnership with Northern Rail. And Rye station, in Sussex, is now home to an architect’s practice that helped make improvements to the fabric of the TOC-staffed station.

Station friends (or ‘adopters’) have brought enormous TLC to hundreds of stations across the network, through artwork, gardens and even poetry. Previously unloved stations in often quite deprived communities such as Westhoughton, Hindley, Mill Hill and Huncoat have been totally transformed by volunteer effort.

And it isn’t just unstaffed stations. Smaller staffed stations such as Glossop, Poulton-le-Fylde, Kidsgrove, Littleborough and Todmorden have benefited from volunteers working with enthusiastic and committed station staff. And there are many more.

New life for old lines

So far, community rail has focused mainly on existing routes, helping to bring life back to forlorn stations and drive up usage. However, the community rail approach can also work for currently abandoned routes such as the Ashington, Blyth and Tyne, March-Wisbech and Skipton-Colne.

The re-opening of the Blackburn-Clitheroe route in 1994 was very much down to local community efforts, assisted by Lancashire County Council and ultimately taken forward with British Rail. And the re-opening of the Borders Railway would not be happening had the Campaign for Borders Rail group not persevered for many years before getting its vision adopted by the Scottish Government.

One of the most exciting projects is the Tavistock re-opening, which is developer-led in partnership with Devon County Council, one of our most proactive local authorities. Devon has already helped to create a market for local rail by focusing housing development around stations that previously served a tiny population.

A good example of this is Newcourt station on the Exeter to Exmouth Line, serving a new community of (eventually) 2,000-plus homes. The station opened on June 4 and is the first in Devon for 20 years - and the sign of things to come for Devon County Council’s Devon Metro plan.

More routes have potential to be brought back into the national network, although no one doubts the huge obstacles that lie in the way. But without grassroots community support that recognises the wider economic and social value of the railway, any possibility of a line re-opening is remote. You also need local authority support and a positive national framework. As Local Enterprise Partnerships (LEPs) take on more transport responsibilities linked to their wider economic development remit, the scope for CRPs to benefit is considerable.

Scorched-earth station

What happens if there are no surviving buildings available to use? Back in the 1960s and 1970s, BR had a ‘scorched-earth’ policy towards its station buildings that resulted in hundreds being torn down as part of its understandable need to reduce costs. As a result, many locations that today might benefit from a staffed booking office or some human presence have no suitable building to house it, and the knee-jerk reaction is that it would be too expensive to provide something.

But it doesn’t have to be so. A highly innovative project in Mid-Wales offers a new approach to the development of small stations, using modular buildings constructed on highly sustainable principles and which offer space for community groups and small businesses. D & S Bamford in Presteigne is developing the ‘caboose’ design (based on the classic BR ‘fitted van’), which could be transported by lorry and put in place at small stations on routes such as the Heart of Wales. So far, the Welsh Government has shown particular interest, together with the DfT and some train operators.

A supportive framework

Having the positive support of the Government, the Office of Rail and Road and Network Rail has been critical. NR recently disbanded its small (but effective) community rail team, and there are concerns that some momentum may be lost as responsibilities devolve to a more local level without an overall strategic focus.

At the DfT, the newly formed Passenger Services (under the leadership of Peter Wilkinson) has been highly supportive of community rail, and pushed the boundaries of not just government thinking, but also Community Rail Partnerships and ACoRP.

The Northern Rail franchise Invitation To Tender is very clear that it expects train operators to come up with innovative approaches to the development of the many community rail lines in the franchise, and in particular make more creative use of stations.

A big question mark hangs over the role of local authorities, who were critical to the success of community rail in the early days and who continue in many cases (for example, Lancashire, Cumbria, Devon and Cornwall) to lead on community rail development.

Cuts in local government funding mean that many ‘non-essential’ budget headings have little chance of survival. In the next few years there are likely to be reductions in local government core funding, although these can be compensated by embedding funding for CRPs in franchise agreements and by linking up with the ‘LEP’ agenda, as well as by looking at ways of generating revenue from a range of activities.

The Settle-Carlisle Railway Development Company is one of the few examples of a CRP that has succeeded in doing this - it runs booking offices, on-train and at-station catering services and marketing activities contracted from the train operator.

There is scope to do more on transport integration, including feeder ‘community transport’ operations, bike hire, and working with commercial bus operators and local authorities to get better synergies between bus and rail.

Stations should be ideal places to base community car projects. For a few years the Penistone Line Partnership ran its own feeder bus service, staffed by volunteers. The basic concept worked, but fell down because of lack of funding and volunteer drivers.

This approach needs to be re-visited, although CRPs could also look at linking up with community car schemes and other forms of innovative provision as the traditional rural bus becomes little more than a memory.

Staff involvement

Railway employees are a vital part of the ‘community’ in community rail, although their contribution is often under-valued. The Penistone Line Partnership is chaired by Northern driver Neil Bentley, while several Northern drivers and guards are often found on the famous Penistone Line music trains.

Many station staff play an active role in working with station friends groups, but there is scope for doing so much more, in co-operation with the train operators, Network Rail and the railway unions.

After more than 20 years’ experience, it is clear that volunteers have no interest in (or intention of) taking over paid railway jobs. It is about ‘additionality’, doing things such as station gardens and artwork and local promotion of the railway, that simply wouldn’t happen otherwise.

A flexible concept

There is no standard ‘product’ delivered by a CRP. Rather, it is about sustainable development in both rural and urban contexts along a railway corridor. It brings in skills focused on community development, regeneration, arts, land use planning and education - as well as transport planning.

The community rail model can be applied to a variety of lines, and has long since moved beyond being just about the rural railway.

For example, in Sussex, community rail exists on busier commuter lines. The same basic principles apply, except that they cannot be designated as ‘lines’ or ‘services’ because of the frequency and speed of services. They still have Station Partnerships (over 50 within the Southern network), and have also raised patronage by above the national average, with passenger satisfaction on the five lines covered by the CRP also well above the average for Southern lines overall.

Funding comes from a wide range of partners, with a lower than average reliance on local government funding, and help from neighbourhood-based parish and town councils as well as private sector partners (including Gatwick Airport).

Even some inter-city routes have good examples of communities working with station staff - for example, Virgin’s Wigan North Western, Rugby and Warrington. And Huddersfield station, operated by First TransPennine Express with nearly five million passengers a year, has an award-winning ‘visitor information point’ staffed by volunteers from Friends of Huddersfield Station.

The role of Huddersfield-based ACoRP in promoting best practice has been essential, and merits recognition. ACoRP’s annual Community Rail Awards (this year to be held in Torquay) showcase best practice and provide a very important celebration of the work of those thousands of volunteers, while its staff and volunteers provide help and assistance to emerging CRPs and projects.

It is an interesting feature of community rail that many of its advocates, in both CRPs themselves and train operators, have been involved for two decades or more. That provides valuable continuity, but also poses the big question of succession planning. ACoRP is currently working with the DfT to develop a ‘community rail apprenticeship scheme’ to train tomorrow’s community rail activists.

Beyond the boundary

Are there ways of getting more out of the ‘community rail’ concept? The answer has to be ‘yes’, although it requires a combination of support from ‘the top’ - the DfT, the devolved governments for Scotland and Wales, and the rail industry - combined with a grassroots willingness to get stuck in and get things done.

The community rail officer of tomorrow will need to be multi-skilled and do a lot more than just promote the local rail service. What he/she does will be determined by local circumstances and partner priorities, rather than a centralist blueprint.

Community rail has moved a long way from being just about unconventional marketing schemes. It is a highly professional but very much bottom-up enterprise in the broadest sense, bringing new thinking to once-neglected parts of the rail network.

It has also stimulated innovation in both infrastructure and technology. The ‘tram-train’ concept came out of ACoRP’s links with well-established projects in Germany, while the ‘Harrington Hump’, which provides affordable level-access ramps at lightly used stations, was another community rail success.

More recently, Vivarail’s project to convert former London Underground D-Stock for regional rail operation is another example of creative ways of applying technological innovation to local railways. The ‘holy grail’ of community rail in the future will be to maintain the ‘community’ aspect and to look at innovative ways of addressing costs of operating local railways without any loss of quality and safety.

Yet there is a degree of frustration, both within the DfT and among Community Rail Partnerships, about the pace of change. We have to find ways of getting things done more quickly, at less cost. Providing a supportive framework through franchising is vital.

The DfT’s ITT for Northern should provide the benchmark for new regional franchises that incorporate significant community rail activity, but there is also scope in longer-distance inter-city franchises and commuter networks.

The ScotRail franchise, specified by Transport Scotland, is highly supportive of community rail, and the franchise agreement includes a £500,000 per year budget. Abellio, the new operator of ScotRail, has gone even further and developed the idea of ‘ScotRail in the Community’, which takes the railway beyond the boundary fence and into neighbourhoods and communities.

And by 2018, when the Wales and Borders franchise comes up for renewal, the Welsh Government will have full responsibility for specifying and awarding the contract.

Wales has several long-standing CRPs, and there is great potential on routes such as the Heart of Wales Line, linking Swansea with Mid-Wales and Shrewsbury. The local CRP - the Heart of Wales Line Forum - has launched a subsidiary regeneration agency (the Heart of Wales Line Enterprise Network, Howlen), which aims to stimulate sustainable development along the rail corridor, focusing on developing station hubs. To succeed, it will need a new approach towards land use planning that ensures that new development - both housing and small business - is located at and around stations.

Howlen is effectively re-creating the 19th century model of rural railway development, whereby entire villages were built up around stations. The vision is of a genuinely sustainable ‘eco-village’ built around the railway, with affordable low-energy homes, co-operatively-run car clubs and cycle provision - and at its heart would be the station, providing shop, office space and community facilities.

The same approach could work on many other rural lines, such as Settle-Carlisle, Cumbrian Coast, East Anglia, Devon and Cornwall branches, and rural routes in Scotland and Wales.

As with so much of community rail, the starting point is getting enthusiastic partners on board, with a shared vision. Community rail is highly professional and has been shown to deliver results. It has got us a long way, but there are plenty more miles for this fascinating train to run.

Peer review: Adrian Shooter

Peer review: Adrian Shooter

Chairman, Vivarail. Former Chairman & MD, Chiltern Railways

Paul Salveson has described the long and tortuous process that has led to the formation of many excellent local groups which have - by their enthusiasm, energy and entrepreneurship - transformed a large number of local lines. I have personally witnessed some of this infectious enthusiasm and noted that many such groups have enabled revenue growth far in excess of the 3% premium that Paul quotes.

Typically, Paul has downplayed his own role in getting this whole movement rolling. For many years after privatisation he was almost a lone voice in promoting a cause that many saw, at best, as marginal. Yet he was well ahead of his time and we now see much enthusiasm for decisions on transport and other issues to be taken locally.

This makes it the more appropriate to observe that, so far, only one half of the equation has been addressed. The original idea behind Community Rail Partnerships was that they would be run by their communities for the benefit of those communities, using local ingenuity to tailor the service and costs to local needs.

We were told about branch lines in Scandinavia where the local bus operator operated and serviced diesel railbuses and (shock horror) ran the trains when they were needed. Somehow all this got lost in the many changes involved in privatisation. It was all too difficult and seen by many as being of little importance.

As a result, we have seen costs of trains spiral out of control, to a point where the cost per seat is almost ten times that of a new bus. Further, we have seen no concerted effort by Railtrack or Network Rail to even identify how you would radically reduce the infrastructure cost of branch lines.

It does not have to be like this. It is now nearly 25 years ago that I first saw one of the Japanese ‘Third Sector’ (= Economic basket case) lines that had been totally transformed. It went from five trains per day, run with few passengers at operationally convenient times (sound familiar?) to an hourly frequency, with supplements to suit school times and other local demands.

The trains were new, smaller and lighter. Instead of trains and staff coming from miles away, they were all based in one small depot on the line. New halts were built next to factories and housing estates, and the whole thing was managed by a recently retired station master from Nagoya (a large local city) and inspired by a board comprising local businesspeople. The resulting operation completely transformed the economy of the valley that it served, in a way that we too could achieve in many places.

In order to get track and signalling costs under control, we only need look to some of the bigger preserved railways in this country for inspiration. It is not difficult! But what can be difficult is the institutional malaise that tends to grip all large organisations, particularly those like NR, who do not face competition.

However, a solution is at hand - now that the Government effectively owns NR, it would be very easy for it to tell the company that it must relinquish day to day control of certain branch lines.

At the point of bidding for a franchise, the industry is at its most innovative and competitive. Therefore, DfT should require bidders to set up (and then transfer to local control) these lines, possibly on a similar basis to my Japanese example. What about the trains? That is why I set up Vivarail Ltd.

Peer review: Peter Wilkinson

Peer review: Peter Wilkinson

Managing Director, Rail Executive – Passenger Services

The origins of community rail can be traced back to the days when there was real fear for the future of rural railways. Fast forward 20 years and Community Rail Partnerships have played their part in turning many lines from moribund backwaters into thriving feeders to the rest of the network of today.

CRPs have successfully harnessed the support of local communities as well as the rail industry, creating the impetus for generating funding for development and improvement of these lines. The key question is how can community rail build on the success of the last 20 years? Success that has resulted in higher growth on these lines, making a positive contribution to the bottom line. Success that has helped to restore redundant station buildings and bring the railway back to being the focal point of the local community.

But having secured the long-term future of these lines we still have some way to go to ensure that they contribute more to the local economy, as well as meeting government’s aspirations on accessibility, the environment and social inclusion.

There is now the case for re-opening and reconnecting parts of the railway lain to the cobwebs, such as Wisbech, Blyth and the missing link between Colne and Skipton. Through combining the managerial skills and finances of franchises with local community endeavour, I firmly believe such partnership will lead to a renaissance of local services and support local economic rejuvenation.

I want to see community railways (and indeed some enthusiast railways) supported through franchising. I believe that we can and should create Social Enterprise businesses within franchises to support these now vitally important railways. Who today would question the value of the Settle- Carlisle Line? And yet not so long ago, the British Railways Board argued for its outright closure. Social Enterprise businesses are not for profit, and at the same time give local communities and innovator/investors a real stake in these railways, from which they can create an investment return, thus allowing new funding to enhance these railways.

I am in favour of seeing a limited number of safe, well-maintained and reliable heritage trains in passenger timetable service on local routes operating within franchises. The public love to travel on these for leisure, pure interest or as part of a holiday. Who should deny them?

Through future franchises, we at Passenger Services are aiming to create the right environment that allows local social enterprises to flourish through taking a stake in their local railway. This is not about fragmenting our network, simply driving down costs; it is about getting greater value, allowing the British entrepreneurial spirit to drive innovation to ensure communities prosper.

Community rail has an important role to play as a catalyst for wider growth and building greater social cohesion and government will play its part to ensure that it flourishes.

Peer review: Stephen Joseph

Peer review: Stephen Joseph

Chief Executive, Campaign for Better Transport

|

Community Rail Partnerships, and their various offspring, such as station adopters, have been a railway success story. They have developed from a handful of volunteer initiatives to an officially endorsed movement with ‘Community Rail’ designations, a national strategy and now strong endorsements and funding in the latest franchise agreements. |

Paul is typically modest about his own contribution. Much of this is down to his own pioneering work on the Penistone Line, to the research he led and to his role in creating the Association of Community Rail Partnerships, now going from strength to strength with DfT funding. There is now a general acceptance that getting communities involved in local railways generates business and goodwill and gives a sense of local ownership.

The question is: where can this go from here? The opportunities presented by stations are clear and the modular station idea sounds great. There are clearly enormous opportunities to integrate local railways more with other transport, especially as the Government starts to look more favourably on bus franchising. We might look to joint rail and bus franchises, especially in more rural areas. Bike hire and car clubs also clearly have opportunities.

Paul is also right about starting to think of railways as spines for sustainable economic development. This will require support from local planners and Local Enterprise Partnerships (who too often tend to think of development as solely around roads and cars). Stations can become centres of their communities, with the use of abandoned buildings for community purposes and development around them for businesses and workshops.

This and other aspects of community rail will be heavily influenced by what happens to local government. Significant cuts in local government funding could undermine some partnerships and (more fundamentally) lead to a withdrawal of some councils from any interest or involvement in their local lines.

However, against this are the wider moves towards devolution to combined authorities and mayors in England. This is leading to devolution of local rail services to groupings of local authorities, notably Rail North and West Midlands Rail. Community rail is going to have to make its case to a whole load of new authorities and people, but the benefits could be enormous in terms of more local attention and control and the “beyond the boundary” strategies, in the way that Paul describes for the Heart of Wales Line.

Paul highlights the importance of community campaigns in getting lines and stations re-opened. Re-openings can’t be looked at in isolation - they need to be part of wider economic strategies linked to development and regeneration.

However, there is one area where CRPs have not yet been able to fulfil their potential - bringing down costs. Micro-franchising hasn’t happened and there has been no serious attempt by the industry to look at ways of running community lines cheaper and better. This is not about reducing services, safety or staff - it’s about making small-scale enhancements without incurring main line-sized costs.

Community rail has a bright future. The question is whether the industry, the Government and local authorities can get together to help it achieve its full potential.

Peer review: Chris Leech

Peer review: Chris Leech

Lead Corporate Adviser to the Transport Sector, BITC

Community Rail Partnerships are one of the UK’s railway success stories, making a real and tangible contribution to local economies and communities along much of our network. Passenger use on community rail lines has grown by nearly 3% a year on top of the ‘normal’ growth on non-CRP lines, so how can we collectively work together to progress this programme, to match the immediate and long-term needs of both the rail sector and the communities it serves?

Greater expectations, scrutiny and pressures are shining a spotlight on how businesses (especially in transport) make their money, on the impact they have on the communities they serve, and on the importance of creating long-term shared value.

If we are to continue on the trajectory created by CRP ambassadors, we need to develop an overarching strategic policy that can be adopted and integrated into business plans by both train operators and infrastructure companies.

The real social and economic gains of such integration are huge. With our network undergoing expansion not seen since the Victorian era, I believe that by working with CRPs, the industry as a whole could not only address the sustainability agenda, but equally it could create a legacy in a way that demonstrates clear and decisive leadership beyond any other sector at a time when it is needed most.

I believe we are now on the way to creating a responsible business approach. The DfT recently announced that ten apprenticeship places will be created for CRPs across the

network. This small step heralds a fresh new approach by the DfT, which recognises that young people have the biggest social network and often the loudest voices within our community. Their ability to transfer information via peer to peer communication is key to taking this agenda to the next level.

We need innovative thinking such as this in order to fill the skills gap, to meet needs and drive future growth. But this could be accelerated even further if we were to adopt a collective responsibility. For example, if we were to provide these young ambassadors with a 360° view of careers and prospects in the UK rail industry, wouldn’t everyone benefit?

Could we harness their knowledge to influence how stations are used, by going beyond the original design to promote community cohesion and increase footfall. Even better, who knows one day we may see stations being effectively managed by CRP groups themselves… the opportunities are boundless.

I now genuinely believe we have the political will and the passion to match those of our excellent teams within CRPs, and extend this hugely successful programme to the next generation of passengers. And in doing so, we are now in a position to communicate and accelerate total long-term value creation.

Business leaders in the rail sector, must be seen to act and demonstrate their commitment to creating a fairer society and a more sustainable future, by fostering a culture that will encourage innovation, reward the right behaviour and rebuild trust. Where better to start than with Community Rail Partnerships?

Login to comment

Comments

No comments have been made yet.