Read the peer reviews for this feature.

Read the peer reviews for this feature.

Download the graphs for this feature.

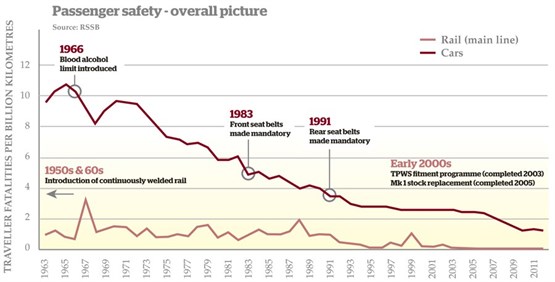

Britain’s rail safety record is impressive. In 2013-14 there were no passenger train derailments, for the first year since records began. We have by far the lowest rate of railway deaths in the EU - three times fewer than Ireland, the next-best country.

Britain is ranked best in Europe at managing passenger and level crossing safety. It is also among the best at managing employee safety.

And yet the Office of Rail Regulation’s annual safety report chides the industry for not doing enough, and demands a sweeping change of culture. It concludes: “We are some way from excellence in health and safety management.”

Is it really worth beating the railway with quite such a big stick, when it is demonstrably a world leader in safety? Britain had more than its fair share of catastrophic crashes in the years following privatisation, but from a passenger’s perspective the recent record has surely been exemplary.

Not so, says the ORR. The trend of steady improvement seen in recent years has slowed, and in 2013-14 it was static. Progress has reached a plateau.

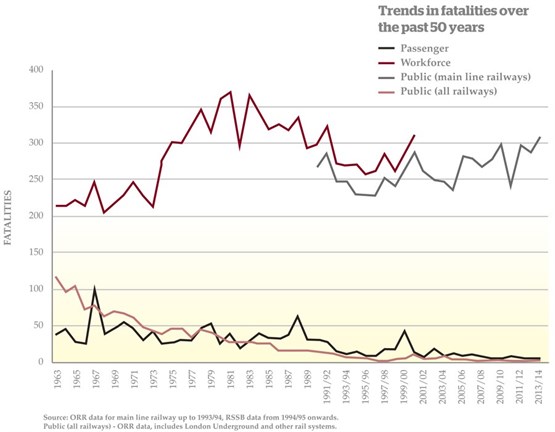

Three track workers lost their lives in incidents that the ORR says were avoidable. Two were road deaths, as people drove home after long shifts on the tracks.

The trend in track workers being injured increased to its highest level in seven years, with 79 workers suffering major injuries and 1,641 reporting minor injuries.

ORR says that although passenger harm fell last year by 9%, workforce harm rose by 10%. In particular, risk of harm to infrastructure workers rose by 22%.

Over the past decade, 20 of the last 25 railway worker deaths have involved infrastructure staff, with 60% of injuries recorded among the same group. Thirty-seven infrastructure workers have been hit by trains in the past ten years, with 11 people killed.

“This is far too high,” concludes the ORR. You can’t disagree.

London Underground

“It doesn’t have to be that way,” says Ian Prosser, director of railway safety and chief inspector of railways at the ORR.

“The main line railway is inconsistent in its approach to safety. It needs to learn lessons from London Underground, which is much better at it. London Underground staff have been better trained, on courses based around NVQs . They understand risks markedly better. The statistics prove it.

“Passengers notice it - they tell you they feel better about it. The platform staff are at the microphone providing guidance, moving people along. They stop people running, they put up barriers and railings in the right places to stop passengers doing the wrong thing, and they manage building work on stations well. LU is better at designing safety into its new work.”

Prosser says he is pleased that Network Rail is now consulting experts at London Underground about how to manage risk more effectively.

“The industry does have a plan. But more people are using stations that were simply not intended for such numbers. We get very large numbers in very short periods of time, and disruption can add to that. Managing people through stations and onto trains is a challenge, especially at stations like Clapham Junction, and we will have to make further improvements.”

If London Underground is best at this, which company is worst? Prosser does not say. But it is clear that he regards the gap between best and worst as pretty wide.

Track workers

“We are still seeing infrastructure workers killed every year, and a stubbornly high number of serious injuries,” remarks Prosser.

“We need a substantial shift in culture. The railway is left like a bomb site after a job, with things just lying around. That doesn’t bring about a culture of safety.

“A lot of the major injuries occur in places where the plans have been changed at the last minute. We need better leadership. We have seen it improve since David Higgins and now Mark Carne has taken over at Network Rail, but we have yet to see that strong leadership reach down to the middle layers of the organisation. There are good plans, but they have yet to be delivered as boots on the ballast.”

For the ORR, Prosser wields considerable power. He serves enforcement notices on Network Rail, requiring it to make changes. If it fails to do so, he can prosecute through the courts, leading to substantial fines. The Regulator can bite as well as bark - and he does.

“We still have men waving flags as the main way to protect track workers. In the 21st century! Really, we can do better than that.”

He says the railway is too reliant on methods that have worked in the past, but which are no longer either cutting-edge or even merely acceptable. As he puts it: “What we see on the ground is an acceptance of what we would call non-compliance.”

In other words, the railway takes a certain level of ignoring current best practice as inevitable, and even acceptable.

“We are still doing things the way they were done a very long time ago. In the 1960s hundreds of people a year died - there is an ingrained culture of accepting standards that should not be accepted. We have to get people to stop doing the wrong things.

We have issued 80 prohibition and improvement notices in the last six years. There has been a lot of enforcement and some important prosecutions.”

ORR welcomes plans for a fundamental change in the role of the COSS (Controller of Site Safety) at Network Rail and its contractors. There are thousands of people doing this work. It wants the person in charge of safety to become much more involved in the planning process, taking responsibility at an earlier stage.

“We have to shift this culture,” says Prosser. “We have to get the guy on the ground in charge and finding better ways for people to look out for each other.”

SPADs

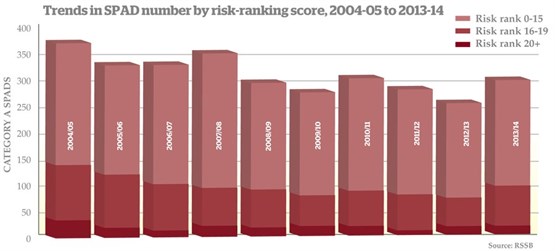

The number of signals passed at danger (SPADs) increased by 17% last year. ORR says train operators should focus on better driver training and management to lower that figure. It is also pressing train operators to upgrade on-board equipment that applies an emergency brake if the driver makes an error.

“As operators lay on more services, drivers will see more red lights. We have to mitigate that as best we can,” says Prosser.

“We thought we might have cracked SPADs. Clearly not. We are very focused on that. It is a grind, trying to encourage the industry to upgrade TPWS where it is getting old. There are better models on the market now.

“We need better understanding of the risk at multi-SPAD locations, and better vigilance in driver management. We have driver management aids now, to monitor how well drivers do. We should use them more.”

The ORR highlights track geometry faults - rail twists - as a particular issue in parts of southern England.

Nationally, Network Rail has been getting a grip on the problem. But not in Sussex, because of “insufficient resources to deal with long-term under-performance, low level of renewals, poor planning and contractor failures, poor track access levels (especially on the Brighton Main Line and inner-London routes), and inherent design problems associated with the south London metro area”.

The ERTMS in-cab signalling system will be rolled out on the Great Western Main Line following electrification, with the East Coast Main Line to follow. This should have a dramatic impact on the number of trains passing red signals. But for much of the rail network it remains years away - perhaps 20 years on some routes. Technology will come to the rescue, but not soon enough for the director of rail safety.

More passengers

Here’s a phrase you will never hear from a passenger about to step off a train: “the platform-train interface”.

The ORR’s media handler apologises for not being able to come up with a better phrase for it. But “Mind the Gap” is every bit as important now as 30 years ago, when BBC Radio Sussex journalist Ian Collington recorded the warning in a voice familiar to generations of commuters.

The ORR says harm to people at the ‘platform-train interface’ increased in 2013-14. Four people died falling from the platform onto the track, and there were 1,250 other platform injuries.

Record passenger numbers makes this “a risk management priority in the short term”, according to the annual safety report. More needs to be done to make platforms safer places for travellers.

The statistics indicate that roughly half the total accident risk to passengers is found here. And 80% of the accident risk is at stations, mostly involving slips, trips and falls on stairs, on escalators and at the platform edge.

But look at the figures in the context of rapid growth in passenger numbers, and a different picture emerges. When measured per passenger, the risk from boarding and alighting from trains actually fell by almost a fifth.

Additionally, over the past decade, two-thirds of all the fatalities involved people who were drunk - 21 of the 32 deaths at the platform edge involved what the ORR calls “passenger intoxication”.

That does not diminish the industry’s responsibility, because it knows that people with impaired judgement frequently choose the train as a safer way home than alternatives. But it does help to explain the extent of the problem.

After the ‘platform train interface’, the next highest area of risk is at level crossings.

Here there is good news: in 2013-14, there was a further reduction of 12% in the level of risk at crossings.

Network Rail has closed 800 crossings in the past five years, and plans to close 500 more in the next five. Britain is comfortably the best in Europe at managing level crossings.

Nevertheless, eight people died on level crossings last year. Two were car occupants at the same incident on an automatic half-barrier crossing, five were pedestrians, and the other was a cyclist. “None were industry-caused,” concludes the safety report.

It is perhaps surprising that the figure was not larger. There were ten collisions between trains and cars at level crossings, and a total of 48 road vehicle incursions onto the track (a drop of 15% on the year before).

“Making crossings safer is not just about closing them, although that is usually the best solution,” says Prosser.

“We call it the Three Es: education, engineering and enforcement. There are some crossings - like Poole High Street in Dorset - where an engineering solution to a high-risk crossing is not possible.

“But we can do more to educate the people who use level crossings. And there should be more enforcement if education is not having sufficient impact. We should not be afraid of tackling people who deliberately do stupid things.”

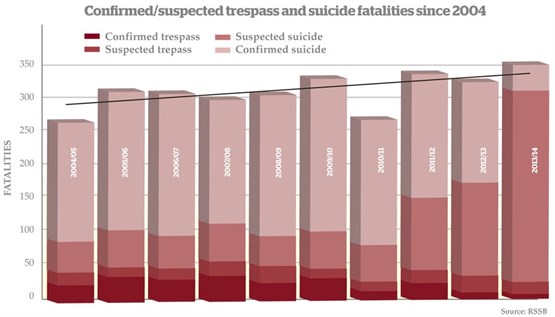

Suicides

The total number of people killed on the railway rose last year. That is primarily due to a greater number of suicides - the highest level for more than a decade.

This is a very sensitive area for the railway. Prosser is keen to highlight the strong leadership demonstrated by Network Rail in tackling the issue, but is wary of the implications of acknowledging that more people are choosing the tracks as the place to end their lives. There were 279 suicides in 2013-14, compared with 246 the previous year. Over the past five years, the rate has risen by 17%. ORR says this is associated with the impact of the global economic downturn, a pattern that is not unique to Britain. Increases in suicides of similar proportions have been recorded in other western European countries.

Four per cent of suicides in Britain occur on the railways. There is a particular incidence of males between the ages of 15 and 44 choosing this location - almost half of all rail suicides are in this group.

“What the industry is trying to do with the Samaritans is really very good,” says Prosser. “There have been many examples of railway staff, trained by the Samaritans, who have intervened in situations where this has led to someone not taking their own life. The numbers are large. There are hundreds of these, and this deserves praise.”

Network Rail recently renewed its training contract with the Samaritans for a further five years. Since 2010, 5,000 front line staff have been trained in active suicide prevention, and in 2013-14 they recorded more than 600 interventions.

“The industry is really well focused on this,” says Prosser. “The training of staff both in prevention and in dealing with the unpleasant aftermath of a suicide is very positive. We know there are particular suicide hotspots, such as railway lines close to psychiatric hospitals, and we need to make sure that more staff in those areas are trained.

“This is a problem that is increasing nationally, but we are being part of the solution. It’s a credit to the industry.”

One piece of good news in this area is that the number of trespassers killed on the railway fell last year - 21 people died, compared with 32 in 2012-13.

The ORR’s annual report concludes that the slowing trend “illustrates that the industry’s work to better control infrastructure access is being increasingly effective”.

Principally that means Network Rail has been installing more robust fencing at the most appropriate sites, particularly on the West Coast Main Line.

Off the pace

Prosser says that the rail industry’s occupational health programme is “some way off the pace” compared with other sectors, such as the petro-chemical industry in which he worked for 18 years.

“Other companies focus enormously on getting safety built into the design of everything new. On the railway we tend to use a tried and tested design because that is what has worked in the past. We have to move on from that. We need a new mindset to make things better from the get-go.

“The industry is good in a crisis - look at what it managed at Dawlish. But it doesn’t step back often enough or early enough at the design stage, such as on a station refurbishment, to incorporate safety improvements. It needs to build for maintainability, for whole life use. It’s not being done consistently. Get that right and the whole railway becomes more cost-effective.”

As an example, Prosser cites electrification work in the North West. Here, his voice changes from his customary quiet monotone. He is astonished at what his inspectors have found.

“We have challenged Network Rail very hard on electrification. Standards are not only inadequate; they are unlawful. We’ve had to enforce. They’re building without much thought about future maintenance.

“Have you seen how they isolate the power on a 25kV overhead wire? They have a remote switch-off. But they earth the cable using a pole. They actually stand there and push up a big stick. It takes a long time, it contravenes electrical standards, and it’s an obvious area where they can make improvements to both safety and efficiency.”

Prosser repeats his observation that LU has much to teach Network Rail about safety. Perhaps that is not surprising - after working for ICI, he worked at Amey Rail and was then safety director at the former Metronet. As he puts it, he worked at the coalface on the underground railway before his current six-year stint as a regulator.

“Last winter, managing the risk during the bad weather was done well. What Network Rail did better was improving engagement with the Met Office, with superior contingency planning. We had embankments slip; we had lots of trees down. But we had fewer and less serious incidents with trains.

“Thinking about where the key risks were, they put watchmen out, they put people on cab rides to detect problems, and they adjusted timetables. We still had trains hitting trees - lots of them - but fewer were serious.”

He highlights the leaf fall season as remaining an unnecessarily large problem. The annual graph for signals passed at red shows a marked autumn spike.

And the ORR believes that Network Rail still needs to improve its management of lineside vegetation. “If it manages vegetation better, SPAD management will improve, too.”

Britain is best

The UK has the best safety record in the EU by a wide margin, both for passenger and workforce fatality rates.

Here, it is just over one death per billion passenger train kilometres. Ireland is next best at 3.4. It’s a big gap to Germany at 11.8 and France at 17.2. Spain scores poorly, as a result of the derailment near Santiago de Compostela in July 2013 that killed 79 people. Countries such as Bulgaria, Romania and Estonia have fatality rates more than 80 times higher than the UK.

Our record is formidable by any standards. Britain is in a league of one. The last death on a passenger train for which the railway was responsible was in the Grayrigg derailment in Cumbria in 2007.

And it is more than a year since a passenger train came off the tracks at all. The two potentially highest risk train accidents last year were freight train derailments at Gloucester and at Camden Town in London. The ORR is still investigating those.

So should the ORR be celebrating the industry’s considerable achievements, rather than continuing to bash it with a very big stick?

“We have been very fortunate with the figures this year,” Prosser explains cautiously.

“You only need one accident for the figures to look very different, and for us to slip down the table. Spain is the obvious example of that. We don’t have many crashes, but when they happen they tend to be catastrophic.

“The Japanese are very good on safety. There has not been a single fatality on the Shinkansen since it opened in 1964. That is the level of safety that we should be aiming for.

“It is so important not to be complacent. Last year’s two freight train derailments could so easily have had very different outcomes. As a regulator I should never be satisfied. I want to see excellence, and I am not seeing excellence consistently across the main line railway.

“It is not about gold-plating the railway, it is about solid, continuous improvement.”

Network Rail has responded to the ORR’s report by stressing its efforts to improve safety.

“We know there is more to do to make the railway even safer for the public, passengers and particularly our workforce,” it says.

“We believe that everyone must return home safe, every day, which is why we have committed to eliminate all fatalities and major injuries among our workforce and the contractors who work for us by 2019. Outstanding safety performance and outstanding business performance go hand in hand.”

When asked whether Network Rail is tiring of being repeatedly mauled in public by the Regulator, Prosser sidesteps the question.

The Office of Rail Regulation’s safety directorate is smaller than it was six years ago. But it still employs 132 staff, which is just under half of the ORR’s total resources. Prosser says that, like Network Rail, it has had to achieve more with less - carrying out investigations faster and more effectively, while ensuring safety inspectors spend at least half their time out of the office, proactively examining the railway.

The ORR has approved more than £250 million of spending to increase protection and warning systems for track workers, plus £100m to close more level crossings. It says it wants to see rapid progress in introducing new technology to reduce risks.

It has established teams focused on Network Rail in the coming year, concentrating on the biggest areas of risk reduction: level crossings, track, civil structures, electrical and workforce safety.

So what will change between now and summer 2015?

“In next year’s report, I think we will still be talking about track workers,” sighs Prosser.

“It’s going to take time to change the culture. Perhaps five years. It is going to be a long grind.

“That is without doubt my biggest goal. And we will very much be talking about the challenges that come from growth, that come from the renaissance of the railways.”

Peer review: Len Porter

Peer review: Len Porter

Former Chief Executive, RSSB

I would like to quote Ian Prosser, then step back a little and look more deeply at those statements and the underlying issues they expose.

- “ORR, like Network Rail, has to achieve more with less.”

- “Concentrating on the biggest areas of risk reduction.”

- “It’s an obvious area where improvements can be made in both safety and efficiency.”

- “Other companies focus on getting safety built into the design of everything new.”

- “It needs to build for maintainability.”

- “We need a better understanding of risk at multi-SPAD locations.”

- “The next highest level of risk is at level crossings.”

The article is written in 2014, but some of the quotes would not have been out of place in 2003. It could be argued, for example, that among other things the Hatfield accident in 2000 was caused by a poor understanding of the concept of risk and, therefore, a risk-based approach to inspection and maintenance.

To really understand risk, it is important to collect the correct data and develop the management systems to convert that data into information. Such information can then be used to populate the risk and reliability models that in turn provide the knowledge for risk and evidence-based decision-making.

In the early 2000s, it was said that there was a lot of data available concerning lock nuts detached from stretcher bar bolts appearing on the ballast. Since the data was not collected and fed into information management systems, there was nothing to alert the management that there was a growing risk of a Potters Bar incident - which eventually happened in 2002.

Perhaps a risk-based inspection approach would have led to the points that caused the Grayrigg accident in 2007 being inspected as a matter of priority, instead of being left because of time constraints.

Over the years, the primary safety-critical industries have learned that safety and efficiency go hand-in-hand. Safety risk is but a part of overall business risk, and safety performance a part of business performance.

If infrastructure and other assets are designed, fabricated and constructed interdependently with ease of installation, commissioning and maintenance in mind, it usually results in a better overall system performance, cost and risk balance.

This is, of course, easier said than done. But such an approach was captured in the first BSI PAS 55 document published in 2004 (updated in 2008), the Institute of Asset Management document Asset Management - An Anatomy published in

December 2011 (version 2 published July 2014), and in the ISO 55000 standard series published earlier this year and which was such an ongoing success for the Institute of Asset Management.

The recently updated and excellent RSSB document Taking Safe Decisions outlines similar principles, and is worthy of an article in its own right in a subsequent version of this publication, since it is so important for the European rail industry regarding risk assessment and evaluation.

Taking a systems-based approach hasn’t been easy, when the nature of franchises and particularly their lengths is considered alongside the Network Rail five-year Control Periods. It has been difficult to achieve efficient working arrangements, common objectives and aligned incentives, and to embrace the true spirit of partnership to include Network Rail, train operators and their joint supply community. Unfortunately an

adversarial approach has often prevailed, with poor contacts and procurement practices making it difficult to deliver whole-of-life value as a result.

Fundamental to a modern asset management approach is achieving a line of sight from industry or company strategy and corporate objectives, through to operational planning.

I believe that the industry has been hampered by poor government intervention and regulatory capability. In an industry with a long-life asset base that needs clear long-term thinking, it is not so long ago (in these terms) that, for example, high-speed rail and electrification were out and then back in again a year or so later.

Unfortunately, the ORR spent a lot of time and effort trying to regulate cost out of Network Rail without regulating good practice in. The Value for Money review contributed little, and probably took the industry backwards rather than forwards.

The good news, however, is that I believe both government and the ORR have substantially shifted their thinking in recent years. The ORR’s CP5 determination was really very good, but it was for CP5 and not CP3 - it asks for the right things from an asset management point of view, but perhaps up to ten years too late.

The DfT has significantly raised its game, reflected in the much improved approach to franchising with (I believe) even better things to come. It is no surprise, therefore, that the industry has relatively recently gained from informed direction and regulatory guidance.

It was heartening to read the August edition of Assets (the Institute of Asset Management magazine). An article entitled The 10-point plan describes the journey and approach to how Network Rail has implemented a significant improvement programme, to transform the way it manages its structures assets. The article is excellent, and should give Ian Prosser and the ORR added confidence that Network Rail is taking a lead going forward and has improved performance at reduced cost and with risk in mind.

During my time at RSSB from 2003 to March 2014, there is no doubt that the GB rail industry improved its safety position significantly for a range of good reasons. But, as illustrated by the PIM, there is underlying risk that has flat-lined and in some cases (for example, risk associated with SPADs and civil assets) recently increased.

Much of the PIM improvement has been the result of engineering intervention and investment in asset renewal - rolling stock, track, TPWS. The next step change, in my view, will come from the use of new data, information and overall asset management systems and associated competencies. These will improve overall performance at reduced cost and risk.

So safety will improve as we get better at managing the asset base and overall system. In the meantime, I have sympathy with Ian’s position, and I especially agree that such a change in culture and approach will take at least five years. I just wish we could have started the journey earlier - the tools and building blocks were there, but not the strategy, direction or informed regulatory guidance to push the industry along.

Peer review: Andrew Evans

Peer review: Andrew Evans

Imperial College London

Improved railway safety is unquestionably a good thing. Therefore, however highly-placed Great Britain may be in the European league tables, where there is scope for further safety improvements, safety regulators have a duty to call for those improvements to be made.

Or do they? What concerns me about Paul’s article, and about the ORR’s Health and Safety Report 2013/14 on which it draws, is the absence of discussion about the scale of safety benefits to be expected from the various safety measures mentioned, or of their costs. It is therefore not possible to form a view about what safety measures give good value for money, and what do not. Instead, the argument is that if the railways are less than excellent in some respects, they should do something about it.

A good example is the number of signals passed at danger (SPADs). RSSB data show that there were 293 SPADs in 2013/14, an increase of 17% on the 250 recorded in the previous year. That sounds like a far from excellent performance, which moreover is getting worse.

However, the latest version of the RSSB’s Safety Risk Model estimates the current fatality risk from train collisions following SPADs as 0.55 fatalities per year. Given that the average fatal train accident causes about four fatalities, that implies a fatal SPAD accident about once every seven years.

In fact, we have done rather better than that. There has been no fatal SPAD since the Train Protection and Warning System (TPWS) provided a step-change in train protection in 2003. That implies that the gains from reducing SPADs are real, but limited.

If SPADs could be reduced by better driver management and training at no additional cost, then it would be a ‘no-brainer’, and the ORR would be right to press for it. However, if additional resources were required, these would need to be compared with the safety improvement.

Paul reports that the regulator is pressing for upgrades to TPWS equipment pending the rollout of ERTMS, which will not be widespread for many years. This appears to be a classic case where the costs need to be compared with the benefits - and given the data, it would be straightforward to carry out.

As for ERTMS itself, RSSB says its expenditure is “far in excess of the financial value of any safety benefit, and therefore it is accepted that the safety benefit should not drive the decision-making process”. The decision was driven by the non-safety business case.

To finish with a different point, the scope of rail safety reporting has been gradually increasing. A notable recent addition is the inclusion of road accidents and casualties to staff in the course of work. This is welcome, and reflects the acceptance by the industry of the need to manage road use.

However, it means that trends in casualties need careful interpretation. A series may rise not because of any real change, but simply because its scope has been widened.

Login to comment

Comments

No comments have been made yet.