Ensuring that risk from all identified hazards is controlled to an acceptable level is fundamental. But this facet should not mask that at their most basic, standards are economic tools to stop solutions being reinvented in multiple and incompatible ways. If standards are thought of as managing risk, it is important that this is seen holistically - ‘risk’ does not mean safety risk alone, it means the risk of not achieving all business objectives, including cost control and service efficiency.

Many standards are prescriptive, to allow the railway to operate as a system. The hidden benefit here is the need to avoid - literally! - re-inventing the wheel.

Imagine the cost if each organisation had to assess every aspect of compatibility, the associated risk and mitigation and the evidence base to underpin its decisions. Yet standards should only be prescriptive when they need to be for a specific economic or safety reason. This is particularly true for the higher-levels standards such as TSIs, where it is the outcome that should be specified, not how this is achieved.

In the framework for a safe and efficient railway, standards sit alongside other components such as legislation, safety management systems and the competencies of people working on the railway.

The regulatory structure defines the roles and responsibilities of industry entities. Each infrastructure manager and railway undertaking is responsible for its part of the system. The law obliges them to implement necessary risk control measures, where appropriate in co-operation with each other.

So standards are an essential element of this risk control regime. The Office of Rail Regulation monitors and enforces compliance with relevant legislation and company safety management systems. It is the essential role of standards in managing risk that places standards on ORR’s agenda. (Note: RSSB has no role in monitoring compliance with standards).

Also in this legislative environment are the Common Safety Method (CSM) regulations. Application of a standard recognised code of practice is one of the three options that a proposer of change can use to illustrate that an identified risk has been controlled to an acceptable level (the other two are using similar reference systems and explicit risk estimation).

So in this legislative environment, it is critical that a standard can firstly be clearly linked to the risk it helps control. This makes it essential for the standard to be developed using a sound process and a robust evidence base. Secondly, it requires the users of the standard to have the competence to assess if the standard addresses the risk adequately, to apply the standard at the appropriate time and correctly, and to understand what additionally needs to be done to control the risk. This places increasing requirements on the competency frameworks in duty holders.

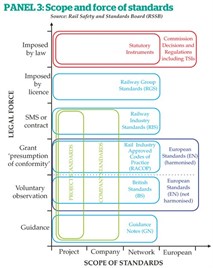

Much of the complexity in standards arises because there are many different types of standard, with differing scope and given force by different means (see Panels 3 and 4). Those with greater scope typically involve interfaces, which is where European and RSSB activity is focused. Where interfaces are not involved, standards are more usually company-specific.

When questioning any standard - whether for clarification, deviation or change - the key questions should always be what does compliance achieve and whose standard is it? These different types of standards themselves create interfaces with the opportunity for conflicting standards.

One significant trigger for change is the introduction of TSIs. From January 1 this year, these now apply across the main line network. Therefore, the work of RSSB has been to align Railway Group Standards with TSIs. This transition has enabled the opportunity to simplify the RGS regime, reducing the number of RGSs from 227 to 112.

RSSB and its members, together with the ORR and DfT, continue to work together to align the requirements of TSIs and the National Technical Rules. This reduces potential confusion and conflict between standards and reduces the potential for unnecessary double assessment of conformity.

The consequence of simplification, reducing standards numbers and a trend towards outcome (rather than prescriptive) standards has seen an increased demand for guidance. Thus Railway Industry Standards (RISs - non-mandatory requirements that can be adopted by companies as their own standard) have been introduced and are increasing in number. Where RISs are used to define good practice, this is positive. However, this should not substitute an organisation’s risk assessment competency or be used to illustrate compliance.

The other focus of the past few years has been the revision of The Rule Book. The Rule Book is unusual among Railway Group Standards in that it contains direct instructions for operational railway staff. While much of the debate around standards concentrates upon asset-based standards, the role of the Rule Book can never be underestimated in not only workforce safety (and the interface with passenger and public safety), but also the efficient operation of the railway.

Individual company standards are also part of the landscape. Inevitably, given the scale of infrastructure, Network Rail standards play a key role. Much work has been done in recent years, both in considering the standard requirements between different types of route and on overall simplification, with Business Critical Rules.

The companies in the UK rail industry have substantial influence on standards - companies set their own standards, decide which Railways Industry Standards (which are not mandatory) to adopt, and directly shape the Railway Group Standards.

For RGS and RIS, RSSB manages a committee for each asset class, comprising industry members across infrastructure managers, train and freight operating companies, ROSCOs, infrastructure contractors and the supply community. The overall strategy for these standards is set by the Industry Standards Co-ordination Committee (ISCC), again with cross-industry representation. The rail industry both defines the standards and the process by which they are set.

The role of RSSB (see Panel 6) is both as expert body and to build the consensus. Experience suggests it is the technical complexity of an issue that is the time-consuming factor, rather than the building of consensus. But consensus is essential, given the role of standards described above in managing efficiency and risk, and for no one part of the system to impose unaccepted requirements on another.

It is true that the main line industry directly shapes its standards. This is also true in Europe (if less apparent). Here, DfT (as the Member State) represents UK rail in negotiations for European standards. However, it is a role directly informed by RSSB, channelling input from members. Each TSI is reviewed by the relevant standards committee or ‘mirror’ group, and a detailed brief prepared.

More than this, RSSB - working with DfT and members - builds allies around the preferred positions. Approximately ten man-years per annum of effort in RSSB is directly attributable to Europe, including representation for work on Euronorms, typically covered by the British Standards Institute (BSI) in other sectors.

Standards may not be perfect. An individual standard is only as good as the expert judgements that have shaped it and the legislation and criteria used as the framework for these judgements. That said, considerable care has been taken in making these judgements, supported wherever possible by evidence.

It is equally true that at any given moment technology, legislative and individual company changes are in progress. Thus there will always be examples of standards that can be revised or improved. The key point is whether examples are isolated or can be generalised to a more fundamental concern.

Let’s consider these in two groups. Firstly, the nature of standards: do standards stifle innovation? Introduce delay? Increase cost? Then secondly, are the framework and processes for making judgements appropriate?

Innovation: Standards do not themselves stifle innovation. Look at the electronics sector - innovation is rapid; product lifecycles are short; new TV sets receive a signal; SD cards and USB storage are compatible. Suppliers innovate because they have to. They operate within the standards they need to (safety and electrical compatibility, for example) and innovate by identifying need and assessing the risks. Standards follow where there is either a benefit or legislation.

This is far from a perfect comparison, but is sufficient to demonstrate that it is not standards themselves that stifle innovation. In rail, the innovation barriers relate more to timeframes and payback, system interoperability, product acceptance processes, and supply chain engagement. What also stifles innovation is buyers specifying too narrowly what they want, rather than defining the problem to be solved.

When standards work at their best they promote innovation by creating a level playing field for suppliers and by specifying the outcome, not the solution. Too often customers fail to work with suppliers, neglect to introduce lean product acceptance processes, and fall back on company standards rather than risk evaluation of new products.

Innovation may be a challenge in rail. The focus and investment of recent years is making good progress, but more has still to be done. Yet standards still do not make it into the top five factors to address for accelerated innovation.