Read the peer reviews for this feature.

Download the graphs for this feature.

Recent research carried out for the Campaign for Better Transport’s Metropolitan Transport Research Unit (Heavy Goods Vehicles - do they pay for the damage they cause? June 2014) used existing Government criteria, and found that HGVs pay less than half of the costs associated with their activities in terms of road congestion, road collisions, road damage and pollution.

These are known as external costs - those costs that HGVs impose on others that are not included (internalised) in their normal operating costs.

Although the financial framework for rail and road is different, it is generally accepted that in both cases, revenues from moving people (in fuel duty, vehicle excise duty and fares) are to some extent used to support the movement of goods.

This report shows the level of distortion of the market across different modes. It suggests that the Government should adopt a holistic approach, treating all modes equally and delivering its policy on a balanced playing field, recognising the value equation between freight subsidy and the direct and indirect benefits to the UK economy. And it demonstrates that for as long as road continues to be so heavily subsidised, it will be very difficult for rail to compete - even though rail use reduces road congestion, is safer and less polluting.

The report also shows that HGVs do not meet their costs by some large margin, using different accepted assumptions. In fact, the report shows that HGVs pay less than 40% of costs imposed on society (an underpayment of about £5 billion a year, using Government assumptions), making a strong argument for sustainable modes being given more support.

The ideal option in terms of economic theory would be to charge road users for their marginal external costs (MECs), such as congestion, environment, climate change, accidents and infrastructure costs. External HGV costs are understood to be high in relation to operator running costs and other vehicle-type externalities. And importantly, rail could replace road on many flows with substantially lower marginal externalities.

The report explores the different approaches that can be used, focusing on what HGV costs are (using existing values from European and UK research) and to what extent taxes and charges cover these costs to assess if HGVs “pay their way”.

It reviews the current status and what might be done in the future, highlighting the benefits of distance-based lorry road user charging, and citing European examples. It evaluates the different accepted Government methods, marginal external cost and fully allocated cost model, and assesses the scale of undercharging using different economic assumptions (see Different costing methods panel, page 41).

The research ultimately highlights that the Government needs to be transparent, so that the level of subsidy is acknowledged and mechanisms can be used to correct these distortions. And the scale of subsidy to road makes a compelling case for supporting sustainable freight modes that impose much lower costs on society and the economy alike.

Government’s mode shift grant values are used to calculate the costs and are designed to recognise the wider advantages of water and rail, but currently support less than 15% of rail traffic, for example.

Mode shift benefit

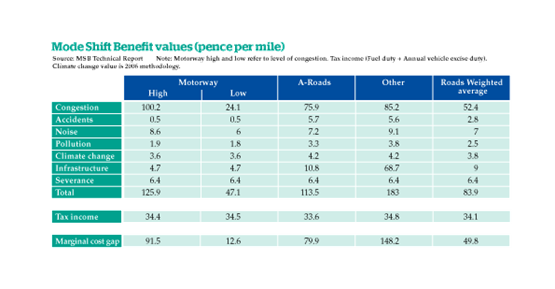

The Mode Shift Benefit (MSB, page 40) is the most recent DfT estimate of average marginal external costs per mile for all articulated HGVs. The average marginal external cost is 83.9 pence per mile in 2010 prices, although there are wide variations on different road types. The tax income from VED and fuel duty is 34p per mile .

However, there are reasons to believe that the current report highlights a number of areas where the Government’s understanding of the costs and impact of lorries is flawed or outdated and that it demonstrates that the current MSB figures need to be revised to better represent the true costs. These include:

- Infrastructure costs: Infrastructure costs from HGVs are falsely low because capital costs of infrastructure are not included. Congestion costs might be disputed, but the capital cost of road building cannot be disclaimed.

Road damage from the heaviest lorries is estimated to be 150,000 times higher than for a typical car, therefore some of the heaviest road repair costs are almost exclusively attributable to the heaviest vehicles.

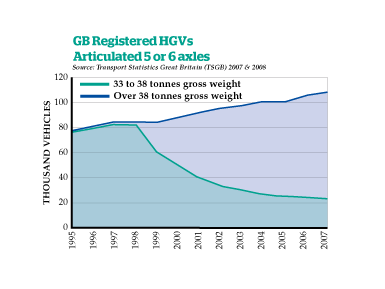

The largest and heaviest HGVs have the highest marginal costs - for example, six-axle articulated HGVs are 2.6 times more damaging than four-axle articulated HGVs. Thus the increase in the proportion of the largest vehicles means an overall increase in damage caused. In the UK, HGVs are hugely concentrated around the maximum limit, which is more damaging for road surfaces (see graph, page 40).

It can be argued that fuel duty does cover maintenance costs on motorways and A-roads, but not capital road costs on any road types. However, on local roads that are not built to the same specification as trunk roads, and are therefore less able to cope with HGVs, neither maintenance nor capital costs are covered.

The DfT mode shift benefit values (MSB, see table page 40) for the different road types highlight this. The costs per mile given for motorways is 4.7p, and for A-roads 10.8p, while all other roads are costed at 68.7p.

It should also be noted that motorways and A-roads represent only around 3% of road miles, so the vast majority of miles driven are on local roads. The worst infrastructure costs of HGVs could be avoided if HGVs stayed on motorways, but they need access to off-motorway depots. Also, the road haulage industry consistently opposes any restrictions on HGV access.

- Collisions: The cost of road collisions involving HGVs are undervalued in the Government’s MSB rates and need to be updated as they do not reflect the DfT’s own statistics.

MSB uses a low value for accidents at 2.8p on average, which is slightly lower than the old values the Government used to use - Sensitive Lorry Miles value (2.9p), and much lower than another study by Mckinnon that had a value of 7.4p.

It is important not to use average figures for accident costs, because the pattern of HGV accidents is different from other vehicles. This is an area where older figures appear to have been updated, rather than refreshed, and further work is required to check the current values.

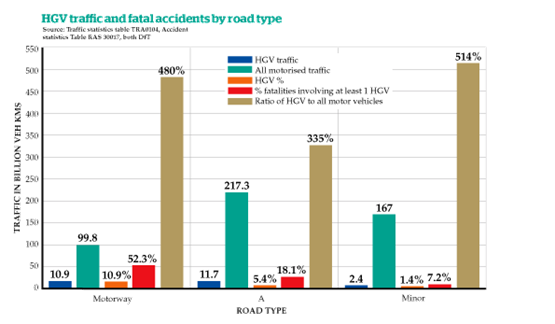

One important factor is that HGVs are five times more likely to be involved in fatal accidents (which have a far higher cost compared with non-fatal) on minor roads. Additionally, the graph on page 43 shows that HGVs are involved in more than half of the fatal collisions on motorways, even though they only make up 11% of miles driven.

All of these figures need to be analysed in the context of latest Government statistics, which reported a 3% increase in road fatalities that translates into 47 more deaths on the roads than in 2012.

- Congestion: Congestion is not properly calculated as government analysis uses undervalued, simplistic and outdated figures to calculate the cost of delays imposed on others. This factor is hugely important, as congestion imposes significant costs to UK plc and is used to justify road building projects - the Freight Transport Association claimed that road congestion cost businesses £24bn per annum in 2011.

Some in the road haulage industry try to claim that congestion costs should not be associated with HGVs. But if that is their argument, they cannot then lobby for more roads to solve congestion.

The passenger car unit (PCU) seeks to define the road space occupied by different vehicles, with the average car as 1. When there is an impact on other traffic, it is clear that this has two elements (Actual length of traffic lane occupied + Time that the lane is occupied), and these two elements need to be calculated.

HGVs are considered to take up almost four times the space of an average car when stationary (PCUs). Then one has to allow for the fact that HGVs are slower to negotiate junctions and need longer front and rear headway than cars as their braking distances are greater.

However, this complexity is not reflected in government analysis. Currently the road space occupied by HGVs measured is only 2.9 PCUs, but it could be at least 4 CPUs on motorways and even higher on local roads.

- Pollution: There is a pressing need to review some impacts such as air pollution. However, we understand that the provisional revised values being considered by the DfT could put air quality costs at zero, which is very worrying, as a TRL report confirms that Euro VI HGV engines will not solve the problem of particulates.

- Climate change: The impact on climate change is also undervalued, with a carbon charge unrepresentatively low because an earlier version of carbon costs was used. The revised values that are being evaluated by the DfT and which are likely to be around 6p per mile, should correct this.

A Government Mode Shift Benefits revision is now being carried out by the DfT, in advance of the new grant regime. Once all these factors are reviewed and re-calculated using updated values, the likelihood is that the real subsidy to HGVs will be shown to be even greater than this research calculated. It would also show that modal shift to rail is even more beneficial to society and the economy.

Without comprehensive HGV distance-based charging, there is a rationale for balancing grants in favour of modes that have lower marginal external costs.

But by introducing a time-based (rather than a distance-based) system this year, the Government has missed an opportunity to create a level playing field for UK hauliers and to make road freight more efficient and sustainable.

A proper distance-based system would have provided an incentive to logistics operators to get better efficiency out of their HGVs - resulting in safer, cleaner and less congested roads - and would have provided an opportunity to charge foreign lorries on the same basis as UK hauliers.

DfT figures show that almost half (46%) of HGVs are partially loaded (in other words, neither constrained by weight nor volume) and almost a third are entirely empty. A distance-based system would reduce road freight inefficiencies such as partial loads, empty running, depot location, port of landing and general logistics practices that would arise from the generation of a freight system working at optimal efficiency.

There is considerable interest at European level in charging road freight vehicles in full for these external costs. In order to include some or all of these costs, there are now different approaches in place across the EU that charge HGVs for road use: motorway tolls in France, Spain and Italy; and ‘in vehicle’ distance charging in Germany, Austria, the Czech Republic, Slovakia and Switzerland. France is currently preparing to introduce an ‘ecotax’ on HGVs on the country’s non-motorway strategic network.

What these charging systems show is that road freight transport demand is relatively ‘elastic’, with demand reacting directly to changes in price.

Road charging is therefore an effective measure to reduce congestion, pollution and accidents from lorries. And the major effect is a reduction in distances travelled by lorries, but not a reduction of tonnage.

Therefore, road charging does not hamper trade. Efficiency within the road freight sector will increase, and the current wasteful planning - manifested especially in poor load factors and empty running - will be tackled as a priority. And since the negative impacts of road freight transport - congestion, accident risk, air and noise pollution -are directly proportionate to total distances driven (vehicle-km), these will also be reduced.

The German Maut lorry charging system, which covers lorry track costs, resulted in an 11% reduction in empty running in a four-year period, to below 20%. It also led to a 2% increase in loaded runs, and a rail freight increase by 7% in the same period.

In the Czech Republic, a km-charge was introduced for vehicles over 12 tonnes on motorways and expressways from January 1 2007. The volume of heavy goods traffic on these roads has since decreased by 10%, even with impressive economic growth rates during that period.

A proper distance-based lorry road user charging system would encourage more efficiency in the road freight sector, by providing a direct stimulus to improving utilisation (load factors) and allowing rail and water to compete with road and aviation.

In the debate on increasing size and weight limits of lorries (for example, mega trucks), proper charging is seen as critical, as these vehicles would impose even heavier costs on the economy.

Otherwise road freight subsidies will increase, and sustainable modes will find it even more difficult to compete even in the traditional bulk cargoes. The current HGV charging regime distorts the market, and leads to poor economic efficiency even though road freight is highly competitive.

Worryingly, as a result of this economic distortion caused by a lack of internalisation of HGV costs, not only is there poor economic efficiency, but also scarce Government resources could be misallocated as funding decisions are made on flawed premises.

This CBT research contributes to a reasoned debate about the value of different freight subsidy choices for the economy and society, allowing the Government to take into account all the costs associated with the different modes.

There are big changes being implemented by the Government, changes that provide the opportunity to progress this debate within the UK.

The Office of Rail Regulation’s role is being expanded to include cross-modal duties, enabling it to consider a broader range of the cross-modal effects resulting from the decisions taken on rail freight charges and structure.

Road charging

For example, ORR will become more aware that any decision that results in modal shift from rail to road will have serious external cost implications for the economy, environment and society. This new road function will increasingly give the Government a vehicle to look at comparative costs across both modes, and in fact ORR could become a de facto freight regulator across road and rail.

The rail freight industry is tabling its amendments on cross-modal duties to the Infrastructure Bill that will facilitate the setting-up of the new body to replace the Highways Agency.

As well as reforming the Highways Agency, the Government is carrying out its review of marginal externalities of road as part of its review of revenue support to rail freight, with the new values currently being appraised by the European Commission for state aid purposes.

Additionally, a European Commission proposal on road charging for both freight and passenger vehicles is anticipated in early 2015. It is expected that the EC will recommend a distance-based charging system throughout the EU, as the best mechanism to ensure that there is better internalisation of costs and to try to get the polluter to pay. Questions should be asked about where the HGV subsidy fits with Government policy, so it can evaluate how to charge the different modes.

Peer review: Richard Wallace

Peer review: Richard Wallace

Former EU Policy Manager, ATOC

Phillippa Edmunds makes some pertinent and very interesting points that are often not widely aired, possibly due to the strong road lobby throughout Europe.

As she says, the cost of damage to local infrastructure by the use of bigger and heavier lorries is nowhere near recouped through either fuel tax or vehicle excise duty. Yet the charging regime for rail freight in Great Britain takes account of both capacity use and the impact of various traffic and vehicles on the network, which surely argues for a comparative system for HGVs if we are to have a level playing field between the modes for the carriage of freight.

The EU’s work on interoperability and a competitive market on rail also advocates the need to reflect a similar charging structure across the European rail network, in order to better reflect the internalisation of external costs. However, when it comes to road freight, it seems that the EU policy is at odds with that for rail - the ‘Eurovignette’, which could eventually introduce a common charging regime on road, has not progressed far as the EU does not wish to make it mandatory.

What is more serious is the EU’s policy on even larger trucks - the so-called mega-trucks of weights up to 60 tonnes and a length of up to 25.25m (over 82 feet).

In 2012, EU Commissioner for Transport Siim Kallas announced a reinterpretation of EU Directive 96/53. This now permits the use of mega-trucks between two Member States that have approved the use of such trucks within their borders. A number of countries (such as Denmark and Germany) are allowing ‘trials’ of these trucks, while others (such as the Netherlands, Sweden and Finland) have now accepted their use. Sweden has even carried out further trials of extra-long mega-trucks of 32.5m in length (over 106 feet) and an 80-tonne payload..

This may well be the thin end of the wedge, as the introduction of such mega-trucks will seriously undermine the viability of rail freight in what is already a very competitive market. The EU’s policy also takes no account of the increased pollution, environmental and structural damage that these larger heavy goods vehicles will inflict, as well as their impact on road safety.

Fortunately, the recent HGV road user levy in the UK is a step in the right direction, while the Department for Transport has come out firmly against mega-trucks. But despite this, road charges that reflect congestion and pollution costs which could address some of these issues have been widely resisted in the UK (with the exception of London).

Phillippa’s article should flag up the need for the rail industry, domestically and EU-wide, to lobby much more strongly for a level playing field for rail, especially if the EU’s goal of shifting 30% of road freight over 300km to other modes (such as rail or waterborne transport) by 2030 is to be realised.

- For more information on the arguments regarding the impact of mega-trucks, download the joint paper on this subject produced by UIC, CER and UNIFE earlier this year. It can be accessed at http://www.uic.org/IMG/pdf/megatrucksbrochure_web.pdf

Peer review: John Smith

Peer review: John Smith

Managing Director, GB Railfreight

A recent analysis by KPMG found that rail freight moves over £30 billion worth of goods per year, generating more than £1.5bn of economic benefits for UK plc through improved productivity and reduced congestion.

The rail freight industry’s ability to maintain this level of contribution to the UK’s economy clearly needs to be supported and Philippa’s article quite rightly draws attention to what has long been suspected as the ‘hidden’ high levels of subsidy received by HGVs.

It has long been my instinct that road is overly subsidised compared with rail and that this has a damaging impact on our ability to compete. But in order for us to establish what a fair playing field for subsidies would look like, there needs to be more transparency when it comes to financial support for road freight.

It is within the Office of Rail Regulation’s remit to ensure cost transparency for the railways, and in this regard we are leaps and bounds ahead of the rest of Europe.

With the restructuring of the Highways Agency and the ORR’s new role in road network management, there is an opportunity to apply the same principles to road freight to give us a better understanding of what the subsidy gap looks like in order to carve a path forward.

But I would go further. As well as a fair playing field for subsidies, we also need to address the problem of capacity on the rail network.

Rail freight is being marginalised by the dramatic increase in passenger services being put forward by the Department for Transport in its franchise proposals. But the Government must appreciate that writing more and more trains into passenger franchise agreements requires parallel investment in infrastructure, in order to help retain freight capacity. This investment must urgently and strategically address the capacity constraints on the network on a key route basis.

The Midland Main Line electrification is an example where 50 years of planning in the Leicestershire quarries has led to an enormous growth in demand for rail freight, which requires parallel investment in Network Rail infrastructure.

F2N is another example of a critical piece of infrastructure investment for the industry, allowing us to support the growth of intermodal traffic on rail, as against road in and out of the Port of Felixstowe. But it is also a good example of where we need to see a joint road and rail policy, where investment in the A14 and the F2N corridor is joined up.

So, while I recognise the damaging impact of road subsidies on our industry’s ability to grow, we need to urgently see the prioritisation of investment in certain key corridors - such as Birmingham-Nuneaton - in order to relieve the capacity constraints that are putting the brakes on our ability to compete with road.

Peer review: Nick Gallop

Peer review: Nick Gallop

Managing Director, Intermodality Ltd

The latest research, as outlined in Philippa’s article, makes another valuable contribution to a debate that shows no sign of immediate resolution.

The rail industry has long argued for a “level playing field” with road haulage and having hosted a workshop in Brussels earlier this year as part of a project for the European Commission on encouraging greater mode shift of freight from road, it is clear that opinions remain deeply divided.

Proponents of rail argue that without the Grail-like level playing field, rail and intermodal services will struggle to compete with road haulage. The road lobby responds that lorries will nearly always be needed to make the first and last part of a freight journey and that even with the best will in the world, the rail network simply doesn’t have the capacity to carry the majority of freight traffic.

Yet the “road vs rail” debate starts to unravel when you then try to discuss how best to combine (rather than substitute) the various modes of transport to mutual benefit.

On the one hand, ‘pure’ rail freight services - moving large volumes of product between rail-linked sites (for example, aggregates from quarries to urban railheads) - may be less concerned about the economics of road haulage, as the relative costs and logistics of moving several thousand tonnes of freight in one train compared with up to 100 lorries will usually see rail winning out. The fears that the introduction of 44-tonne lorries would wipe out rail freight services proved to be wide of the mark for this very reason.

On the other hand, most of the growth in Network Rail’s latest rail freight forecasts is expected to come from the intermodal sector, where road haulage will be needed at either or both ends of the rail haul. These local collection and delivery trips by lorry make a significant dent in the overall economics of intermodal freight services, against the equivalent door-to-door road haulage price.

In the short term, it is difficult to see how the costs of rail freight could be made significantly cheaper, given that track access charges are already based on the marginal (rather than full) costs of wear and tear. And as Philippa notes, Government continues to provide revenue support for intermodal and other rail freight services (with little way of really knowing whether or not the train operators genuinely need such support). So if the costs of road haulage were then to increase, that dent in the economics of intermodal freight then gets larger.

Heavier and longer lorries bring similar challenges, with the debate generating emotive epithets from detractors, such as “juggernauts”, “mega-trucks” and “gigaliners”, compared with the more warm and fuzzy “European modular concept” used by supporters of longer trucks.

The basic issue is this: if you use a container or swap body to move freight, you will be carrying several tonnes of extra tare weight in the road mode (the container and road trailer weigh more than a standard road trailer), which then eats into your payload, particularly if you’re moving bulk goods.

The UK briefly tried offering hauliers involved in rail freight an extra three tonnes of extra gross weight to overcome this. But the derogation was soon cancelled when the authorities realised (by accident or design – you be the judge) that they couldn’t effectively police the derogation, so the entire industry got the extra three tonnes instead.

Those promoting longer and/or heavier lorries say that this would make the costs of road haulage to and from railheads come down, as fewer lorry trips would be required. Not so fast, says the rail freight industry - this will then make general road haulage more cost-effective, meaning rail will struggle even more to compete. So the debate is unresolved.

Polarising the issues into quasi-pantomime heroes and villains risks missing out on pragmatic solutions, such as Malcolm Group’s inspired decision to use the current UK trials of longer semi-trailers to allow use of longer swap bodies by road - and by rail.

With the UK “blessed” with a fleet of intermodal wagons with 16 metre decks (as BR thought the Channel Tunnel would make us all go continental and start using pairs of short swap bodies - which we didn’t), each time a wagon carries a standard 13.6m-long swap body, that’s over 2m of wasted deck space. It doesn’t sound much, but multiply that by more than 30 times (as most intermodal trains now do), and that’s a big waste of space in terms of the extra swap bodies that could have been carried in the same length of train. But rather than bemoan road hauliers being given another carrot, Malcolm Group now uses the same carrot on rail, too. Simples!

Stepping outside of the ring, the overall challenge must surely be to make logistics as sustainable as possible, minimising the overall level of resources needed to move a given volume of goods (I’m going to conveniently side-step the wider issue of where and how those goods are resourced and manufactured, as there are only so many hours in the day).

This will increasingly mean making use of multiple modes of transport in combination. So any solution for infrastructure charging in one mode will need to avoid unintended consequences in encouraging the right mix of other modes. Philippa notes the apparent success of developments in Germany and the Czech Republic in promoting behavioural change in the use of road haulage and rail freight, suggesting that these problems may not be insuperable.

The European White Paper on Transport notes that “a transformation of the European transport system will only be possible through a combination of manifold initiatives at all levels”. It’s hard to disagree with the sentiment. In North America, intermodal rail freight has seen a dramatic turnaround in fortunes since the 1980s, with a virtually bankrupt and dysfunctional rail sector transformed into a key player in the overland freight market, where legislation is now focused on limiting its scope for market dominance. It’s apparent that Europe (where rail’s market share is around half that in North America) still has a long way to go, and there is no denying that a solution to the challenges of infrastructure charging needs to be found - if nothing else, it can achieve a simple charging mechanism, which avoids the need for further grants and subsidies (and attendant administrative costs) to act as sticking plasters.

Beyond this, achieving a step-change in rail freight use will need its own combination of manifold initiatives – better service quality, faster or higher-capacity trains (and perhaps more dedicated lines for them to run on), quicker border crossings, and more rail freight interchanges. We perhaps need to become more successful at being more North American than any of the North Americans that have tried so far over here (Wisconsin Central, Thrall, Parsec, NDX…)

Login to comment

Comments

No comments have been made yet.