Outright sales are not the only form of privatisation recently seen on UK railways. In 2010, the Government sold a 30-year concession to operate High Speed 1 (the international line from St Pancras to the Channel Tunnel). Government remains the owner, and expects the line to be returned in 2040 in the same condition as at the start of the concession. This leaves operation, maintenance and renewals in the hands of the concessionaire.

The key difference, however, is that as a newly-built railway, HS1 was transferred in a known condition, and is not expected to need enhancing in the next 30 years. The same cannot be said for domestic UK lines, although with long-term deals, a concession could provide the means to fund enhancements.

It’s a model that could have been applied to Chiltern Railways and its line from London Marylebone to Birmingham Moor Street. This route was subject to a total modernisation of track, signalling and trains under British Rail in the early 1990s.

Train services switched to the private sector in 1996, and the operator secured a unique 20-year deal in 2002. This has enabled it to embark on a phased upgrade programme to improve track capacity and station capacity and it’s now laying a new line at Bicester to allow trains to serve Oxford. Funding for the latest work is coming from Network Rail, with Chiltern and subsequent franchisees reimbursing it over 30 years.

Relatively self-contained, a concession could work… subject to agreement about how improvements that outlast the concession itself are treated when the deal expires.

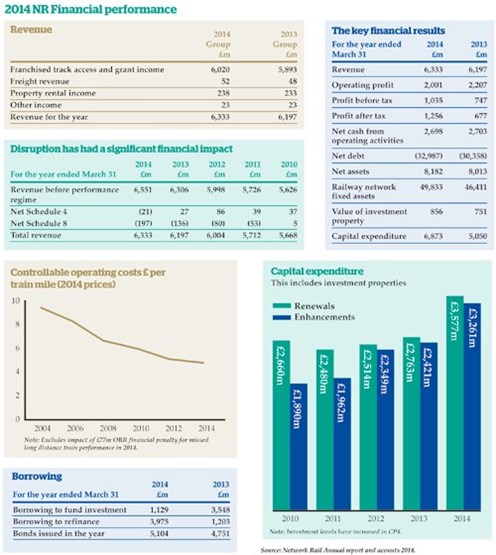

Should government decide that it wishes to continue following EU directives and keep tracks and trains financially separate, it could simply return Network Rail to the private sector with an outright sale. What price ministers might receive for a company with debts of over £30bn is open to question, although they would most likely have removed those debts from their books before any sale. They might even look to sweeten the deal by writing off some of those debts.

It could privatise the company on a regional basis, with the national company’s debts then split either on an arbitrary track mileage basis or (perhaps more fairly) on the basis of the proportion of recent enhancement work that triggered the debts.

But whatever the financial complications of such a sell-off, it’s unlikely to remove the railways from the political sphere. Ministers will still be fielding questions about rail performance. If events go badly, they will be blamed because they sold the company. And if events go the same way for the public sector NR, they will still be blamed. Essentially, selling NR only achieves the effect of taking its debts off the Government’s books (and they were only put there by changes to EU accounting rules).

It doesn’t appear worth the Government’s while to go through what is bound to be a politically complex problem of privatisation, let alone the problems of regional splits of debts or funding. It would take a brave minister to push through such a programme.

The gorilla in the room

From the railway’s perspective, NR (whether public or private) will remain the gorilla in the room, able to sit exactly where it pleases if it remains a national company rather than being split. It could still dominate the train operators and still pay more attention to its shareholders than its customers.

Privatisation does not appear to be the obvious answer to the problem of NR’s failing enhancement programme. So if ‘something must be done’, what that something is in the long term currently remains the key unanswered question.

In the short term, NR and DfT must rigorously examine that failing programme. It’s running out of control and is taking NR’s costs with it. NR has tried to tame it by postponing work, but it’s now time for a complete examination because postponement just delays the inevitable implosion.

DfT must look at what it asked of the railway in its 2012 High Level Output Specification. It must decide which of its demands remain feasible and which remain important, and must cut from the programme that which satisfies neither criteria.

What is clear is that the railway cannot carry on regardless. It is accumulating problems, and if nothing is done those problems will bite hard. Passengers have been promised improvements and they have been told that fare rises are paying for them.

If the railway and the Government cannot deliver, then they must be open and honest - explain the problem and explain their proposed answer. It might be painful… it might be embarrassing… but it must be done.