Paonessa takes up a wider project management thread: “Now the other element is that the process overall just can’t cater for every single incident. You can’t continge for everything. So where we have a big Kirow crane - yes, we’re going to have fitters on site and, yes, we’re going to have people who can do running repairs. But if we have a catastrophic failure of a Kirow there is no contingency plan, because we can’t put two spare cranes on site when we only have three in the country.

“There are some that we just can’t mitigate for. But what we’re now doing, since Christmas, is having another look back at that overall integrated process and saying that if you put the passenger at the heart of that, how do we minimise the disruption to passengers. We either do that from having a fantastic operational recovery plan, if it is possible to do that, or we have to put additional layers of contingency into the project plans. All of which on the project side can cost money… and a considerable amount of money.

“We had a very good example at Wimbledon just after Christmas. We had a planned blockade of five weekends to replace the six sets of S&Cs at Wimbledon, which have sat there since the 1980s and are in quite poor condition with wooden sleepers. It causes lots of operational issues for South West Trains, so it’s a highly critical job.

“The dilemma with Wimbledon, and the reason it’s been deferred so many times, is that it’s difficult to access Wimbledon. If you have a problem at Wimbledon, you not only block Waterloo, you trap SWT trains in the depot.

Schedule risk analysis

“There really is no operational contingency plan that can cope with blocking Wimbledon, so we had another look at the Schedule Risk Analysis for the job and said well, we’re planning to do two point ends, one point end, two point ends, one point end and some follow-up work, but we can actually only safely do one point end (actually, it’s two points - one crossing) per weekend. That adds 30% to the cost.

“So when I say there are real costs in raising the probability of handback from P90 to P95 to P99, they are real and they are quite significant. So we are working on a more sophisticated process that can balance that triangle of the passenger TOC, the operational contingency plan and the project contingency plan, with the costs sitting somewhere in the middle of that.”

Probability runs solidly through project management. What are the chances of all tasks being completed correctly and on time? And, if not, how long will it take to find and correct any errors? For example, in the 5,000-plus words of this article you should (hopefully) find no spelling or typographical errors. You can be pretty certain that the first draft had some of both, which were all later found and corrected.

So it was with Paddington. Critical to this job was checking the changes made to signalling as a result of the changes made to track layouts. Only once all these changes had been made, checked, corrected as required and then checked again could the railway re-open. There were, says Paonessa, something like 10,000 checks to be made.

Under a series of testers-in-charge at Paddington, checks were made and defects reported. Paonessa recounts what was happening:

“Those defects are being loaded into the forward work bank. You’re munching your way through a process that gets you to a point, when you’ve finished, where there’s an hour’s worth of shuffling a stack of paper. And the stack of paper fills three A4 lever arch files - it’s not a simple piece of paper with one tick on it.

“But when you get into those last two hours, if in pulling it all together you find that you have additional work that you need to do, or work that you haven’t completed and you need to go back out and do that, then you need a heck of a lot more time than shuffling the stack together and putting the final tick on it.”

He continues: “So we got to the end of the process - we thought we’d got to the end - and at 0330 the tester-in-charge thought they had an hour’s worth of snagging together. But in going through and carrying out that final detailed check, they found there were some additional things that needed to be done. We had to send people back out onto the railway, so we had to take some possessions.

“As it turned out, we had deferred some overhead line work which wasn’t critical to the handback. We’d deferred that, and since we thought we’d finished testing we put a whole load more MEWPs (Mobile Elevated Work Platforms) back out to do some of that overhead line work. We’d now deployed MEWPs in the area, but we needed to do some wheels-free testing, so we had to get them back off the line as well.

“There were lots of things that stacked up into this process, all of which was around finding testing that was either incomplete or needed to be redone to satisfy the tester-in-charge that what he was handing back was safe to do so.

“Quite a long complex story in all of that, which ends up in a huge amount of detail that doesn’t really help the travelling passenger much at the end of the day. We thought we’d got there and then we found we weren’t. And, of course, we found we weren’t just at the point we were supposed to be handing back.

“That’s what caused such significant difficulties in coming up with an operational contingency plan. We gave the train operators no notice, so we had a fair bit of criticism for First Great Western drivers sitting at signals thinking they were going to be 30 minutes because our best view at that time was that it was going to be 30 minutes.

“It’s a very, very difficult balance when the whole safety of the railway and that whole process is sitting with one individual, and they’re saying it’s going to take 30 minutes. At what point do you stop them and spend an hour trying to understand exactly where we are? Because that’s an hour lost. Or do you leave them with it and let them finish? That’s a really difficult balance to make.

“The team on the ground figured that at 0830 that was the time we needed to stop, draw stumps, and have a long hard think about exactly where are we with the knowledge that we had.”

It must be said that the complexity at Paddington - the 10,000 checks - is hardly unique. Other projects have similar challenges yet are delivered on time. With some pushing, Paonessa concedes that it was “the volume of time that we had to start with and the volume of work that we had to do”.

He adds: “The stack-up of bits that went in there. To be perfectly honest, the process didn’t work as effectively as it could have done because we ended up with a situation at the end where the tester-in-charge thought the work was done, and when we did that final evaluation we found that it wasn’t. There is absolutely a piece in there about the management process that sits around the management of that scope of work.”

Compromise at King's Cross

That balance between volume of work and time available is a theme that runs through Paonessa’s interview. NR wanted four days of full closure for its King’s Cross renewals job - it ended up with two days of complete closure and two days of partial closure. With the West Coast Main Line also closed, a full four days was not available. NR had said after 2007’s problems that it would not have both Anglo-Scottish routes closed at the same time. The clear message from Paonessa is that meeting this requirement compromised NR’s chance of completing its King’s Cross work.

“I think I’d say a couple of things. One is that I think Network Rail and the train operators, and the freight operators, do a great job on a daily basis in minimising the impact of quite a large number of incidents that happen on the railway that are not of our control or of our making.

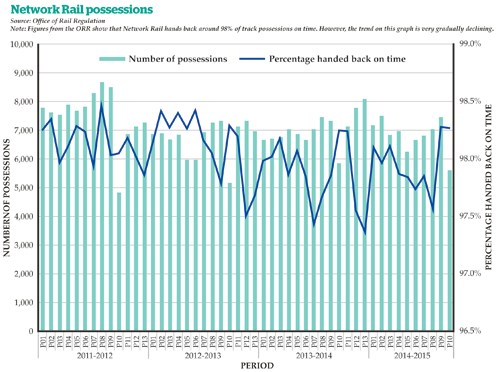

“Christmas and the Bank Holiday periods really complicate that because we have so many areas where we are working. We had 2,000 worksites just as infrastructure projects at Christmas, across 800 possessions. Every single one of those is affecting the railway.

“I think the key part that came out of the report was yes, we look at operational plans and yes, we look at project delivery plans, but our focus is to remember why we have those two and to set ourselves at the top as the passenger, and say: OK, we’ve got this plan and we’ve got that plan, how do they add up to make sure that we minimise disruption to a passenger either through a great plan or a great project delivery plan that has great certainty of delivering.

“Recognising that with the Wimbledon discussion - the more certainty you want of the delivery plan, the more it will cost. And the travelling public wants and quite rightly demands that the railway costs less to operate. So we end up with much tighter boundaries and much tighter constraints, and people have higher expectations. You can’t fault that, but it is a much more difficult circle to square every single weekend.”

NR has long tried to squeeze major engineering work into holiday periods such as Christmas, Easter and Bank Holidays, when fewer commuters will be affected. It also provides the opportunity for longer closures.

ORR’s investigation into the Christmas problems exposed one of the difficulties with the broad assumption that fewer people travel. The days of most disruption were Saturday December 27 and Sunday December 28. For First Great Western, its overall numbers were down - 158,000 passengers over December 27-28 compared with an average weekend of 242,000. But East Coast had more passengers than it would normally expect on a weekend - 84,000 compared with 76,000. (FGW had more delayed passengers, but news coverage focused on Finsbury Park/King’s Cross, probably because there was warning of this overrun.)

The best time to close a line

Even if the broad assumption of fewer travellers is more generally correct than it was at Christmas, it’s fair to say that weekend and holiday passengers will have more bags and be less experienced than the everyday commuters who so skew overall passenger figures. In other words, the railway may find it easier to re-route regular commuters for a period because they will learn a new (if only temporary) routine in a way a heavily loaded occasional traveller will not.